When a patient says, "This generic pill makes me feel weird," it’s not just a complaint-it’s a safety signal. And the pharmacist is often the first, and sometimes the only, person who hears it. For all the talk about bioequivalence and cost savings, generic medications aren’t perfect copies. Small differences in fillers, coatings, or manufacturing processes can trigger unexpected reactions. But if no one reports those reactions, regulators never see the pattern. That’s where pharmacists come in-not as bystanders, but as essential safety monitors.

Why Generic Medications Need Extra Scrutiny

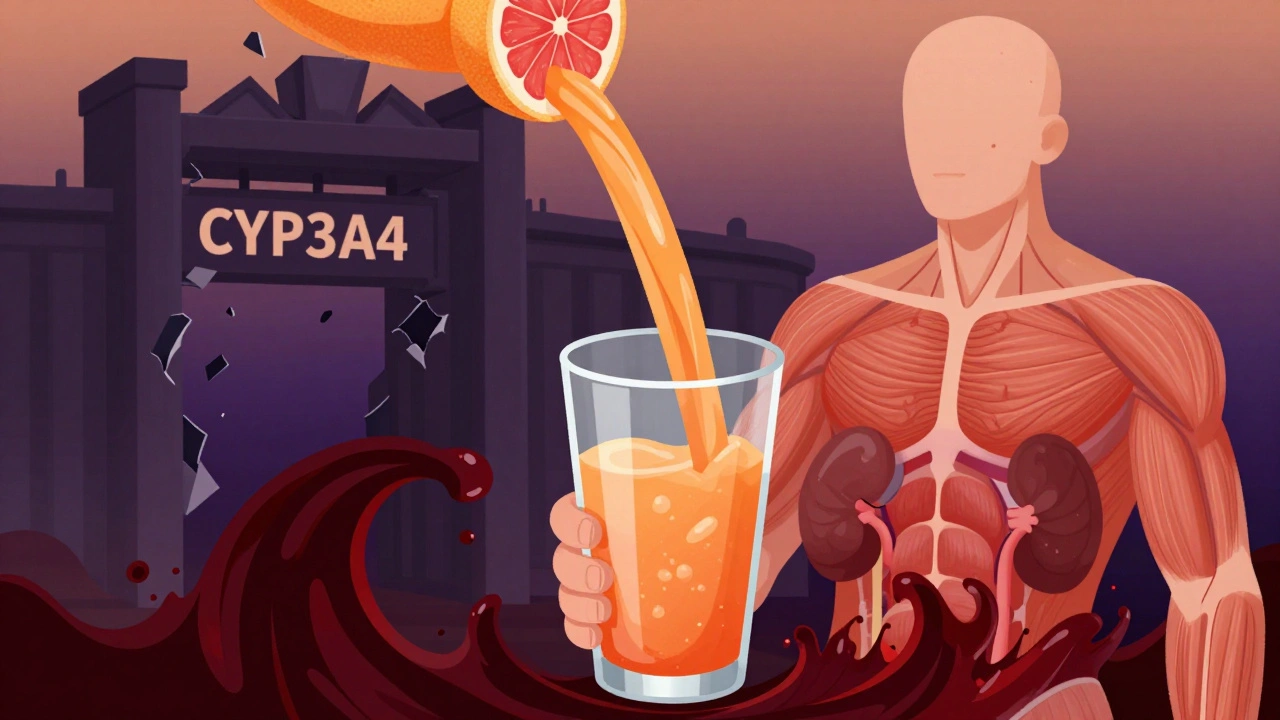

People assume generics are identical to brand-name drugs. They’re not. The FDA requires generics to have the same active ingredient, strength, dosage form, and route of administration. But they don’t have to match the brand in inactive ingredients-things like dyes, preservatives, or binders. These excipients can cause allergies, digestive upset, or even neurological symptoms in sensitive patients. A 2022 study in the Journal of the American Pharmacists Association found that 1 in 5 patients who switched to a generic version reported new or worsening side effects. Many of these weren’t listed in the drug’s package insert. Why? Because clinical trials for generics focus on blood levels, not real-world patient experiences. That gap is where pharmacists step in. When a patient says, "I’ve been on this generic for three months and just started getting headaches," that’s not just bad luck. It’s a red flag. Pharmacists are trained to connect the dots between a patient’s symptoms, their medication history, and potential drug interactions. No other healthcare provider sees the full picture of what’s in the bottle and how it’s being taken.What Pharmacists Are Legally Required to Do

Rules vary by state, but the core responsibility is clear: if you suspect an adverse reaction, you must document it and report it. In British Columbia, pharmacists are legally required under Section 12(7) of the Health Professions Act Bylaws to:- Notify the patient’s prescriber

- Record the reaction in PharmaNet

- Report it directly to Health Canada

The Real Barrier: Time, Not Will

Most pharmacists want to report. But they’re stretched thin. A 2021 survey by the National Community Pharmacists Association found that 78% of community pharmacists spend 15 to 30 minutes per adverse event report. That’s time that could’ve been spent counseling patients, filling prescriptions, or managing inventory. And 62% said they simply didn’t have enough time during their shift. Add to that the confusion around what counts as reportable. Is a mild rash after switching generics serious enough? What if the patient says it went away after switching back? Many pharmacists don’t report these because they’re unsure if it’s "real" or just a coincidence. The British Columbia Pharmacists Association calls this lack of awareness a "recognized problem." Training isn’t built into most pharmacy curriculums. Pharmacists aren’t taught how to distinguish between expected side effects (like drowsiness from antihistamines) and true adverse reactions (like sudden confusion after starting a new generic thyroid med).

How to Report: Step by Step

You don’t need a PhD in pharmacovigilance. Here’s how to report an adverse event in five clear steps:- Identify the reaction. Ask: "Is this new? Is it unusual? Did it start after the switch to generic?" Document the symptom, timing, and severity.

- Confirm the medication. Note the exact name, manufacturer, lot number, and dosage. Generic brands vary-what works for one patient might not work for another.

- Notify the prescriber. Call or send a secure message. They need to know in case other patients are affected.

- Record it. Enter it into the pharmacy system or patient chart. Use clear language: "Patient reported nausea and dizziness after switching from Brand-X to Generic-Y on 02/01/2026. Symptoms resolved after returning to Brand-X."

- Report it. Use MedWatch Online (FDA’s portal) or your state’s system. If unsure, report anyway. The FDA prefers over-reporting over under-reporting.

What Happens After You Report

Once you submit a report, it enters FAERS. The FDA doesn’t confirm causation-they look for signals. If 50+ reports cluster around the same generic drug and the same symptom, they investigate. That’s how recalls start. That’s how labeling changes happen. In 2021, the FDA reviewed 347 reports of hypoglycemia linked to a specific generic metformin. After testing, they found a manufacturing issue with the tablet’s coating that caused uneven release. The drug was relabeled. Patients were warned. All because pharmacists spoke up. The European Medicines Agency saw a 220% increase in reporting after making it mandatory for all healthcare providers in 2012. The U.S. is heading there too. By 2025, analysts predict 75% of U.S. states will adopt rules similar to British Columbia’s.

Why This Matters More for Generics

Brand-name drugs have years of post-market data. Generics don’t. They’re approved based on bioequivalence studies-usually under 100 patients, over a few weeks. Real-world use? Millions of people, over years. That’s where problems hide. Dr. Michael Cohen of the Institute for Safe Medication Practices says it best: "When patients experience unexpected reactions to generics, pharmacists are often the first to recognize potential bioequivalence issues or excipient-related problems that might not be immediately apparent to prescribers." A patient on a generic statin might develop muscle pain. Their doctor assumes it’s aging. The pharmacist knows the brand-name version never caused that. That’s the difference.What’s Changing Now

Technology is helping. The FDA’s MedWatch Online system now handles 43% of healthcare professional reports-up from 29% in 2020. The National Association of Boards of Pharmacy has integrated reporting tools into pharmacy software in 32 states. In pilot programs, reporting time dropped by 40%. The FDA’s Sentinel Initiative is now pulling data from community pharmacies to monitor real-time safety trends. That means your reports aren’t just sitting in a database-they’re being used to protect patients today.Final Thought: Your Report Could Save a Life

You don’t need to be a scientist. You don’t need extra training. You just need to pay attention. Every time you hear, "This doesn’t feel right," you have a choice: shrug it off, or act. Because behind every adverse event report is a patient who might have been ignored. And behind every pattern of reports? A hidden risk that could be fixed before it hurts someone else. The system doesn’t work without you. Not the regulators. Not the manufacturers. Not the doctors. Pharmacists are the missing link in generic medication safety-and that responsibility isn’t optional. It’s professional.Do pharmacists have to report adverse events by law?

It depends on the state. In British Columbia, it’s legally required. In most U.S. states, it’s not mandatory, but the FDA strongly encourages reporting of serious adverse events. Even where not required by law, professional ethics and patient safety standards expect pharmacists to report suspected reactions.

What counts as a serious adverse event?

The FDA defines serious adverse events as those that result in hospitalization, disability, congenital anomaly, life-threatening conditions, or death. Even if a reaction doesn’t meet this threshold, if it’s unexpected and linked to a generic medication, it should still be reported. Patterns matter.

Can I report an adverse event if I’m not sure it’s caused by the drug?

Yes. The FDA’s motto is "When in doubt, report." You don’t need to prove causation. You only need to suspect a connection. Your report adds data to a larger pool that regulators use to spot trends. Many drug safety discoveries started with a single uncertain report.

How do I report an adverse event?

Use the FDA’s MedWatch Online portal (https://www.fda.gov/safety/medwatch-fda-safety-reporting-program) or your state’s system. You’ll need the patient’s age, gender, drug name, manufacturer, lot number, symptoms, timing, and outcome. If you’re unsure, contact your state board of pharmacy-they can guide you.

Why aren’t more pharmacists reporting?

Time constraints are the biggest barrier. Many pharmacists spend 15-30 minutes per report, and most don’t have dedicated time for it. Lack of training on what counts as reportable and confusion about legal requirements also contribute. Only 28% of pharmacists consistently report non-serious but unexpected reactions, according to a 2022 study.

steve sunio

February 14, 2026 AT 04:20Neha Motiwala

February 14, 2026 AT 05:40Robert Petersen

February 15, 2026 AT 14:31Craig Staszak

February 16, 2026 AT 12:58alex clo

February 17, 2026 AT 20:51Alyssa Williams

February 19, 2026 AT 18:59Ernie Simsek

February 20, 2026 AT 06:23Joanne Tan

February 21, 2026 AT 23:19Stacie Willhite

February 23, 2026 AT 07:24Sonja Stoces

February 23, 2026 AT 23:28