Every time you pick up a prescription, there’s a good chance the pharmacist hands you a generic version instead of the brand-name drug your doctor wrote on the script. That’s legal - and common. But it’s not always automatic. You have the right to say no. And if you’ve ever felt confused, pressured, or even scared after a medication switch, you’re not alone. Millions of people in the U.S. are unknowingly being switched from brand-name drugs to generics without their consent - and some pay the price in side effects, unstable health, or lost trust.

What Is Generic Substitution, Really?

Generic substitution means a pharmacist swaps your prescribed brand-name drug for a cheaper version that contains the same active ingredient. It’s not a random decision. Every state has its own rules about when and how this can happen. The goal? Save money. And it works: generics cost 80-85% less than brand-name drugs. In 2023, 92% of all prescriptions filled in the U.S. were generics. That’s $1.3 trillion in projected savings by 2032, according to the Congressional Budget Office. But here’s the catch: not all drugs are created equal. For some medications - like thyroid pills, seizure drugs, or insulin - even tiny differences in how the drug is made can cause big problems. That’s because these are narrow therapeutic index (NTI) drugs. They work in a very precise range. Too little? The condition flares up. Too much? You get dangerous side effects. The FDA says generics are therapeutically equivalent, but doctors and patients know from experience that switching can disrupt stability.Your Legal Right to Say No

You don’t have to accept a generic drug. Ever. And you don’t need to be rude or argumentative to enforce that right. In 43 states, simply saying, “I decline substitution,” is legally enough to stop the switch. Pharmacists are trained to respect that. But not all of them know the law - or choose to ignore it. Seven states and Washington, D.C. go even further. In Alaska, Connecticut, Hawaii, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Vermont, pharmacists must get your explicit consent before swapping your brand-name drug. That means they can’t just hand you the generic and say, “Your insurance prefers it.” They have to ask: “Do you want this generic instead?” And if you say no - they must fill the brand. In 19 states, including California, Texas, and New York, substitution is mandatory unless the doctor writes “dispense as written.” That means if your doctor didn’t check that box, the pharmacy can switch your drug - even if you never agreed. But even in those states, you can still refuse. The law doesn’t take your right away. It just makes you speak up.When You Should Always Ask for the Brand

Some drugs are too risky to switch. The FDA and state pharmacy boards keep lists of these. If your medication is on one, you should never accept a generic without a clear medical reason.- Thyroid meds (like Synthroid or Levothyroxine): Even small changes in absorption can cause fatigue, weight gain, or heart palpitations. Many patients report feeling worse after switching.

- Antiepileptic drugs (like Lamictal or Dilantin): Seizures can return if the generic isn’t absorbed the same way. Kentucky, Hawaii, and several other states ban substitution for these without doctor and patient approval.

- Biosimilars (like Basaglar instead of Lantus insulin): These aren’t generics. They’re complex biologic drugs made from living cells. The FDA says they’re similar, but many patients report blood sugar swings after switching. Only 38 states require pharmacists to tell your doctor when they swap a biosimilar.

- Heart medications (like Digoxin): Too much or too little can be life-threatening. Many cardiologists refuse to allow substitution.

What to Do at the Pharmacy Counter

You don’t need to be a legal expert to protect yourself. Here’s how to handle it:- Know your state’s rules. Check your state pharmacy board’s website. If you live in a state that requires consent (like Massachusetts), you’re protected. If you’re in a mandatory substitution state (like Texas), you still have the right to refuse.

- Speak up clearly. When the pharmacist says, “We can give you a cheaper version,” say: “I decline substitution.” Don’t say, “I’d prefer…” or “Can I get…?” Be direct. It’s your right.

- Ask for the manager. If the pharmacist says, “I have to substitute,” they’re wrong. Politely ask to speak with the pharmacy manager. Most managers know the law better than front-line staff.

- Get a note from your doctor. If you’re on an NTI drug, ask your doctor to write “Dispense as Written” or “Brand Medically Necessary” on the prescription. This removes all doubt.

- Keep records. Write down the date, drug name, and what was handed to you. If you get the wrong drug and have a bad reaction, this could be critical.

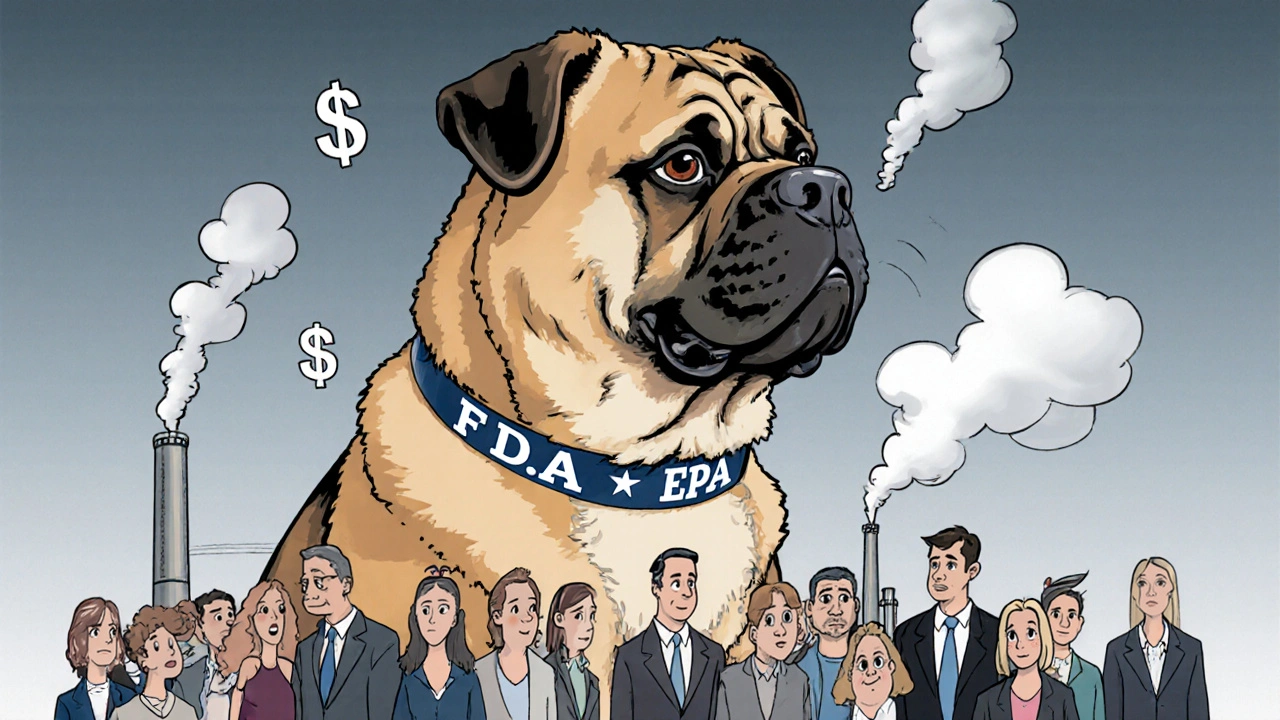

Why Pharmacists Push Substitution - And What They’re Not Telling You

Pharmacists aren’t trying to harm you. Most believe they’re helping by cutting costs. But they’re also caught in a system pushed by Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs) like CVS Caremark and Express Scripts. These companies negotiate discounts with drugmakers and get paid more when generics are used. They even have “gag clauses” - rules that used to prevent pharmacists from telling you that paying cash for the brand might be cheaper than your insurance co-pay. That changed in 2018. The Know the Lowest Price Act banned those gag clauses. Now, pharmacists can legally say: “The brand costs $30 cash. Your co-pay is $45.” If you’re paying out of pocket, always ask. You might save money by choosing the brand. Also, some pharmacies stock only generics because they’re cheaper to buy. If you ask for the brand and they say, “We don’t carry it,” they’re lying. They can order it. It just takes longer. Push back. Say, “I need this filled today. Can you get it?”What Happens When Substitution Goes Wrong

Stories like this aren’t rare. In 2019, a Michigan woman had a seizure after her pharmacy switched her antiepileptic drug without telling her. She sued. The pharmacy lost. In 2021, a survey by Consumer Reports found 28% of patients who tried to refuse substitution were told they “had to” accept it - even though that’s illegal in their state. On Reddit’s r/Pharmacy, people share stories of switching from Synthroid to a generic and gaining 20 pounds, or going from Lantus to Basaglar and struggling with nighttime lows. One user wrote: “I didn’t know the difference until my blood sugar crashed at 3 a.m. I thought I was doing something wrong - until I checked my prescription.” The truth? For most people, generics work fine. But for others - especially those with chronic conditions - the switch can be dangerous. And if no one tells you it’s happening, you’ll never know why you feel off.

How to Protect Yourself Long-Term

Don’t wait for a bad reaction to learn your rights. Do this now:- Check your state’s generic substitution law. Search “[Your State] pharmacy board generic substitution.”

- Ask your doctor to write “Dispense as Written” on prescriptions for NTI drugs.

- Use GoodRx or SingleCare to compare cash prices. Sometimes the brand is cheaper than your co-pay.

- Keep a medication log. Note the drug name, manufacturer, and how you feel. If you notice a change after a refill, you’ll know if it’s the generic.

- Report problems. If you’re switched without consent and have a bad reaction, file a complaint with your state pharmacy board. They investigate these cases.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can my pharmacy refuse to fill my brand-name prescription if I refuse the generic?

No. If you refuse generic substitution, the pharmacy must fill the brand-name drug your doctor prescribed - unless they don’t have it in stock. In that case, they must either order it or transfer the prescription to another pharmacy that does. Refusing to fill a valid prescription because you won’t accept a generic is illegal and can be reported to your state pharmacy board.

Is it true that generics are always just as good as brand-name drugs?

For most medications, yes. But for narrow therapeutic index (NTI) drugs - like levothyroxine, digoxin, or certain seizure medications - even small differences in how the body absorbs the drug can cause serious problems. The FDA considers generics therapeutically equivalent, but patient experiences and medical studies show that switching can lead to instability in chronic conditions. Always discuss NTI drugs with your doctor before accepting a generic.

Can my insurance force me to take a generic?

Insurance can encourage or incentivize generics, but they can’t force you to take one. If your doctor writes “Dispense as Written,” your insurance must cover the brand-name drug. If they deny coverage, you can appeal. Many insurers have exceptions for patients who’ve had bad reactions to generics or have medical documentation supporting brand necessity.

What’s the difference between a generic and a biosimilar?

Generics are exact chemical copies of small-molecule drugs. Biosimilars are similar - but not identical - copies of complex biologic drugs made from living cells, like insulin or Humira. They’re not interchangeable by default. Many states require extra steps before substituting biosimilars, including notifying your doctor. Always confirm whether your drug is a biosimilar before accepting a switch.

How do I know if my drug is on the narrow therapeutic index list?

Ask your pharmacist or doctor. You can also check the FDA’s Orange Book, which lists therapeutic equivalence ratings. Drugs rated “AB” are generally substitutable. Drugs with no rating or “BN” (like many antiepileptics) are often non-substitutable. If your drug is used for a serious condition and you’ve been stable on it, assume it’s high-risk unless told otherwise.

Nicole K.

December 29, 2025 AT 21:35People don’t realize they’re being manipulated. Pharmacies don’t care if you feel like crap after switching - they just want the rebate. I’ve seen moms cry because their kid’s seizures came back after a 'generic' swap. It’s not just money - it’s negligence wrapped in a coupon.

Stop letting them treat your health like a spreadsheet. Say 'I decline substitution' - and mean it. No excuses.

Teresa Rodriguez leon

December 29, 2025 AT 22:38I was switched from Lamictal to a generic and ended up in the ER. No one warned me. No one asked. I just got a different pill and was told 'it’s the same.' It’s not. My brain knows the difference. Now I carry my prescription in my wallet and show it to every pharmacist. I’m not taking chances again.

Russell Thomas

December 31, 2025 AT 04:58Oh wow, another ‘I’m a victim of Big Pharma’ post. Let me guess - you also think your thyroid meds are magic and the FDA is in cahoots with Big Generic? Newsflash: 92% of people take generics just fine. Your body’s just weak. Or maybe you’re one of those people who blame every burp on a pill change.

Next time, try not being a drama queen. And maybe read the FDA’s actual data instead of Reddit stories.

Joe Kwon

January 1, 2026 AT 17:28As a clinical pharmacist, I want to clarify something: the FDA’s therapeutic equivalence ratings (AB, BN, etc.) are based on bioequivalence studies - not anecdotal reports. That said, NTI drugs like levothyroxine and phenytoin do have higher inter-patient variability, and pharmacovigilance data supports patient-reported instability post-switch.

Best practice? If a patient has a documented history of instability, DAW1 is clinically indicated. Insurance doesn’t override medical necessity. We’re trained to honor that. If a tech says ‘you have to take the generic,’ they’re misinformed - escalate to the pharmacist on duty.

Also - yes, cash price checks via GoodRx often reveal the brand is cheaper than your copay. Always ask.

Amy Cannon

January 2, 2026 AT 00:38It is truly a travesty, if you will, that the American healthcare system has devolved into a profit-driven machine where the sanctity of individual patient stability is sacrificed for the sake of corporate margins. I mean, think about it - we have entire populations being switched from life-sustaining medications without so much as a consent form, and yet we praise ourselves for being the most advanced medical nation on earth.

It is not merely a legal issue - it is a moral failing. One must ask oneself: if your grandmother were on Synthroid, would you allow a stranger behind a counter to swap her medicine because it’s cheaper? I think not.

And yes, I did spell ‘travesty’ correctly. And I do not use emojis. Because this is serious.

Himanshu Singh

January 3, 2026 AT 21:53Wow this is so helpful! I just found out my insulin was switched and I didn’t even know! Thank you so much for sharing. I’m from India and we don’t have this issue much here, but now I know what to do if I ever move to US. God bless you all for speaking up!

Jasmine Yule

January 5, 2026 AT 14:33Jim Rice just said generics are fine for everyone? Bro. Have you ever had a seizure? Or a thyroid crash? Or spent three nights in the hospital because your blood sugar dropped to 38? No? Then don’t speak. I’ve been fighting this for 8 years. I’ve called state boards. I’ve emailed senators. I’ve written letters to pharmacy chains.

You think this is drama? This is survival. I’m not asking for permission. I’m claiming my right. And if you don’t like it? Tough. My life isn’t a cost-saving experiment.

Greg Quinn

January 7, 2026 AT 02:33It’s funny how we treat medicine like a commodity. We buy pills like we buy coffee - assuming they’re interchangeable. But the body isn’t a vending machine. It remembers. It adapts. And when you mess with something that’s finely tuned - like thyroid or epilepsy meds - it doesn’t just ‘adjust.’ It rebels.

Maybe the real question isn’t ‘why do generics sometimes fail?’ but ‘why do we assume they always work?’

Lisa Dore

January 8, 2026 AT 22:39Hey everyone - if you’re new to this, start with your state pharmacy board website. They have free PDFs on substitution laws. Also, ask your doctor to write ‘DAW 1’ on your script - that’s the code that says ‘no substitution.’

And if you’re scared to speak up at the pharmacy? Bring a friend. Or text your doctor’s office and have them call ahead. You’re not alone. We’ve all been there. Let’s keep sharing what works.

Sharleen Luciano

January 10, 2026 AT 01:50How anyone can be this naive about pharmaceuticals is beyond me. You think the FDA actually tests every generic batch for bioequivalence? Please. They rely on manufacturer data - the same companies that profit from generics. And you’re just supposed to trust them? How quaint.

And let’s not pretend this is about patient safety. It’s about PBMs squeezing every last cent. If you’re on an NTI drug and you’re not demanding the brand, you’re not a patient - you’re a revenue stream.

Jim Rice

January 11, 2026 AT 18:28So you want to pay $200 for a brand when the generic is $15? Cool. Go ahead. Then complain when your insurance hikes your premiums next year. It’s not the pharmacist’s fault you can’t budget. And if you ‘feel worse’ on a generic, maybe it’s your anxiety talking. Or your diet. Or your sleep. Not the pill.

Stop making medicine a personal crusade. It’s not a religious relic. It’s chemistry.

Henriette Barrows

January 13, 2026 AT 05:38My mom was switched from Lantus to Basaglar and started having crazy lows at night. We didn’t know why until she found this post. We called the pharmacy, showed them the FDA’s biosimilar guidelines, and they ordered the brand. Took 2 days. Worth it.

Just say ‘I decline substitution’ - it’s that simple. No drama. No yelling. Just a calm, clear sentence. And if they push back? Ask for the manager. They always know the law better than the tech.

Thank you for writing this. I’m sharing it with everyone I know.