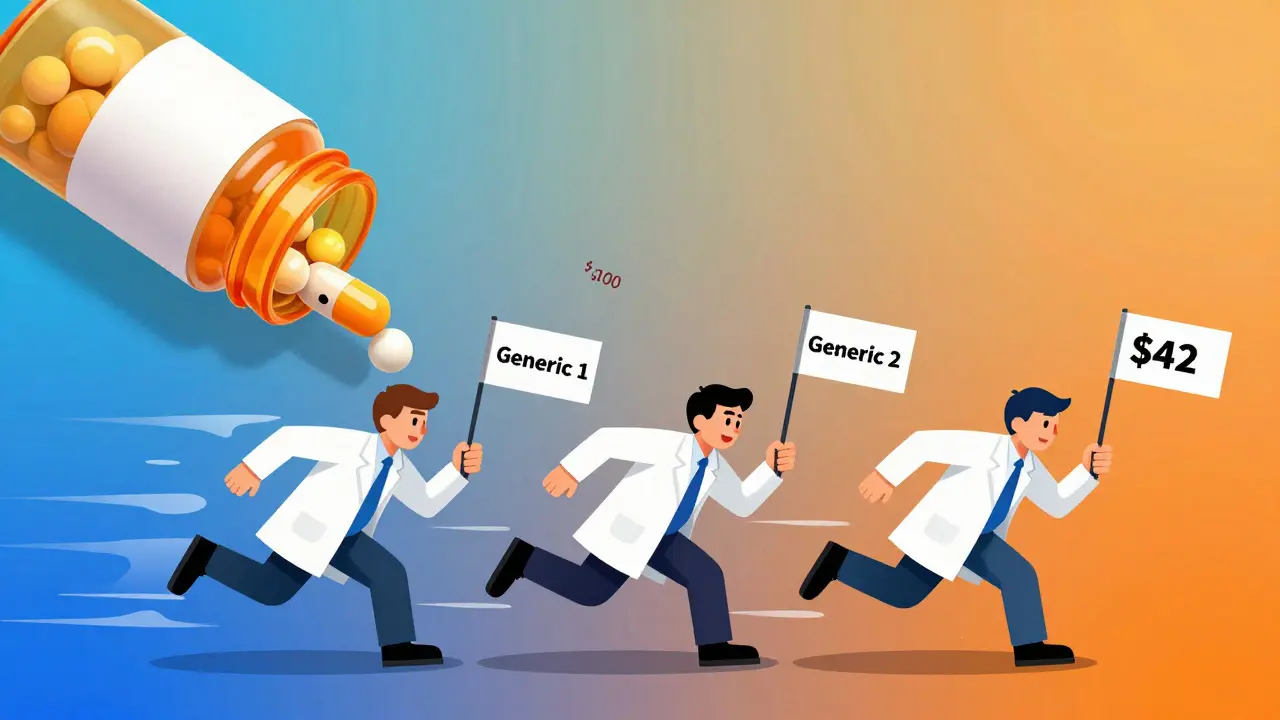

When a brand-name drug loses its patent, the first generic version usually hits the market at about 13% off the original price. That sounds good-but it’s just the beginning. The real savings come when a second and then a third generic manufacturer enters the race. That’s when prices don’t just dip-they plunge.

Why the second generic changes everything

The first generic company often has a head start. They’ve done the work to get FDA approval, built relationships with distributors, and maybe even got a short-term monopoly. But they’re not the only ones who can make the same pill. Once the second company enters, prices drop sharply. According to FDA data from 2022, the second generic brings prices down to about 58% of the original brand price. That’s not a small discount-it’s more than half off. Why? Because now there’s competition. The first generic company can’t just sit back and charge what they want. If they keep prices high, the second company will undercut them. And they know it. So they lower their price. Sometimes, they drop it by 20% or more just to stay in the game. This isn’t theory. It’s data. A 2021 analysis by the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (ASPE) found that in markets with three generic manufacturers, prices fell by about 20% within three years. But that’s just the start.The third generic hits the floor

Add a third manufacturer, and the price drops even further-to 42% of the brand’s original price. That’s a 27% additional cut from the second generic’s price point. In real dollars, that means a $100 pill now costs $42. For patients paying out of pocket, that’s life-changing. The effect isn’t linear. It’s explosive. The jump from one to two generics saves money. But the jump from two to three? That’s where the biggest savings happen. Why? Because now the market is no longer a duopoly. It’s a true auction. Each manufacturer knows that if they don’t keep their price low, they’ll lose market share to someone else. And with three or more players, the pressure to cut costs becomes relentless. This is why markets with just two generic makers are dangerous. A 2017 University of Florida study found that nearly half of all generic drug markets were stuck in this two-company trap. And when competition drops from three to two, prices don’t just stop falling-they often rise. Some drugs saw price spikes of 100% to 300% when one manufacturer left the market. That’s not a glitch. It’s how monopolies work-even in generics.What happens when 10 companies enter the race?

The savings don’t stop at three. In large markets-where a drug is prescribed to more than 15,000 people a month-you often see 8, 10, even 15 different generic makers. In those cases, prices can fall to 70-80% below the original brand price. That’s not a discount. That’s a revolution. These markets are where the real savings happen for the whole system. The FDA estimates that between 2018 and 2020, the 2,400 new generic drugs approved saved patients and insurers $265 billion. Most of that came from competition among multiple manufacturers, not just the first one. But here’s the catch: not all drugs get this kind of competition. Complex drugs-like injectables, inhalers, or those with tricky manufacturing processes-often have only one or two makers. That’s because it’s expensive and hard to copy them. That’s why the FDA launched GDUFA III in 2023: to speed up approvals for these harder-to-make generics and bring more competition to markets that need it most.

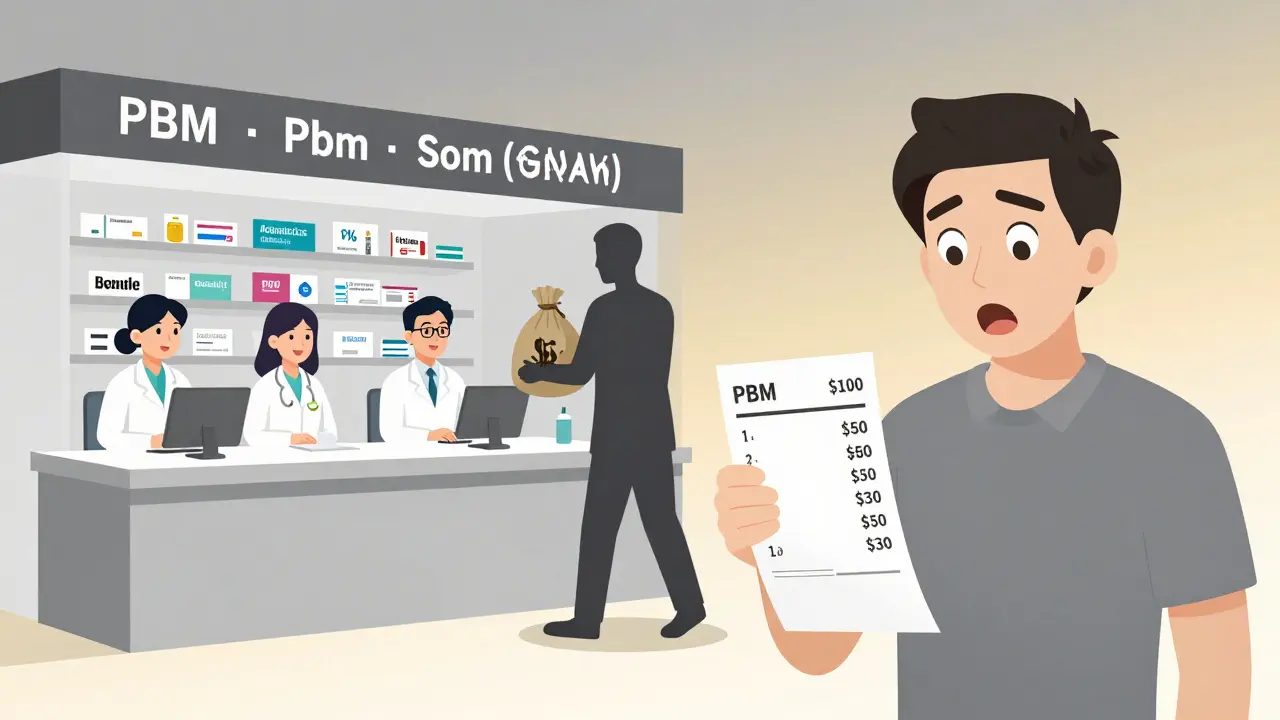

Who’s really benefiting?

You might think the savings go straight to the patient. But that’s not always true. The price drop happens at the manufacturer level. Then the drug moves through a chain: wholesalers, pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs), and pharmacies. The Big Three wholesalers-McKesson, AmerisourceBergen, and Cardinal Health-control 85% of the market. PBMs like Express Scripts and CVS Health process 80% of prescriptions. These middlemen often negotiate discounts with manufacturers. But they don’t always pass those savings on. A 2019 FDA analysis found that while manufacturer prices dropped 60-70% with multiple generics, pharmacy acquisition costs only fell 40-50%. The difference? Wholesaler markups and PBM fees. That’s why some patients still pay too much. But here’s the good news: when competition is strong, PBMs have more leverage. Evernorth Health Services found that when five or more generic makers are available, PBMs get better discounts. And those discounts can translate into lower copays-if the plan design allows it.The dark side: how big pharma fights back

You’d think more competition would be a good thing. And it is. But brand-name drugmakers don’t like it. They’ve spent billions fighting it. One tactic? “Pay for delay.” That’s when a brand company pays a generic maker to stay out of the market. The FDA and the FTC have called this illegal. But it still happens. The Blue Cross Blue Shield Association estimates these deals cost patients $3 billion a year in extra out-of-pocket costs. Another tactic? “Patent thicketing.” A single drug might have dozens of patents-some for the pill, some for the coating, some for the packaging. In one case, a drug had 75 patents that stretched its monopoly from 2016 all the way to 2034. That’s not innovation. That’s legal obstruction. Congress has tried to fix this. The CREATES Act (2022) blocks brand companies from refusing to sell samples to generic makers. The Preserve Access to Affordable Generics Act targets pay-for-delay deals. But enforcement is slow. And the market is still rigged in places.

What’s next for generic pricing?

The trend is clear: more competitors = lower prices. But consolidation is making it harder. Teva bought Allergan Generics. Viatris formed from Mylan and Upjohn. Fewer companies mean fewer entries. That’s why experts warn: if we don’t protect competition, prices will stabilize-or even rise. Analysts at Evaluate Pharma predict generic prices will keep falling 3-5% a year through 2027. But only if new manufacturers keep entering. If the market gets too concentrated, we’ll see more duopolies. And that means more price spikes. The bottom line? The second and third generic entrants are the most powerful tool we have to lower drug costs. They’re not just alternatives-they’re economic engines. Every time another company gets FDA approval, patients win.What you can do

If you’re paying for prescriptions:- Ask your pharmacist if there’s more than one generic available. If only one, ask why.

- Compare prices at different pharmacies. Some chains have better deals on certain generics.

- Use mail-order or discount programs like GoodRx. They often show the lowest price among competing makers.

- Speak up. If your insurance won’t cover a cheaper generic, ask them why. Demand transparency.

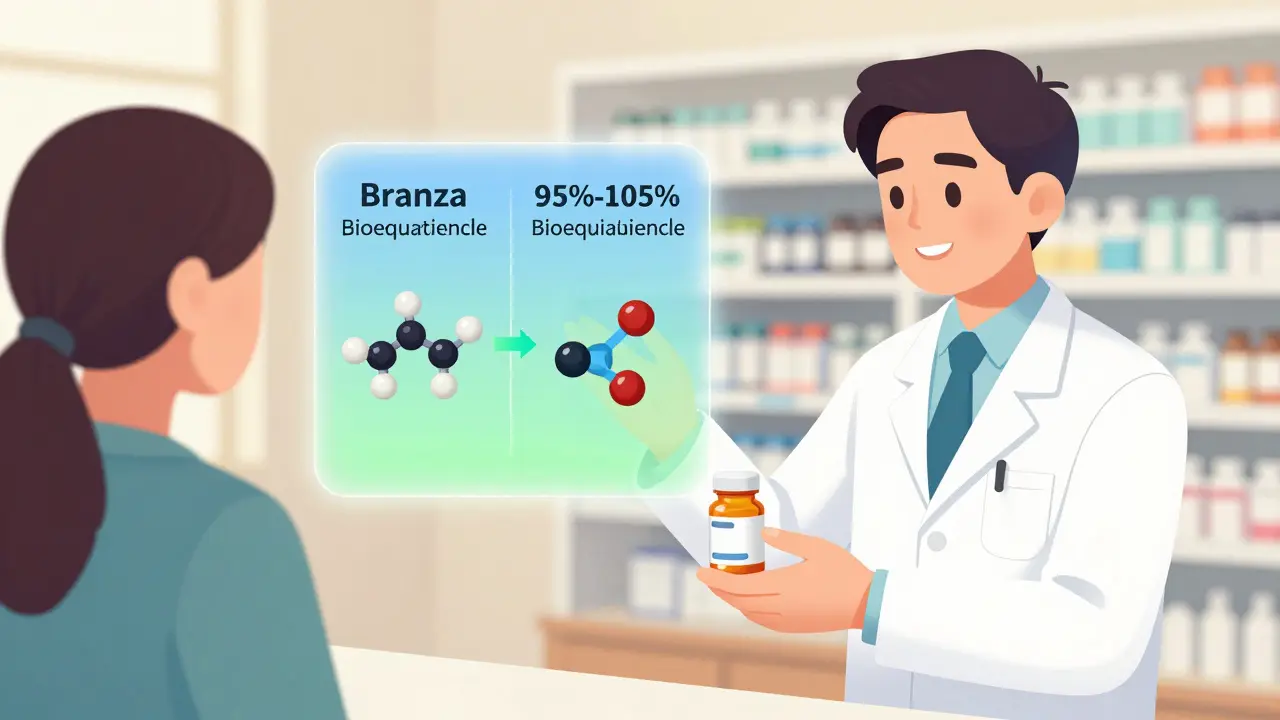

Why do drug prices drop more after the second generic enters?

The first generic often has a temporary advantage-early approval, established distribution, or even a deal with a pharmacy benefit manager. But once a second company enters, they compete directly on price. To stay competitive, the first generic must lower its price. This triggers a chain reaction: prices fall by about 36% from the brand level. The second generic doesn’t just match the first-it undercuts it. That’s why the drop from one to two generics is steeper than from brand to first generic.

Does adding a third generic always lower prices further?

Almost always. FDA data shows that the third generic drives prices down to 42% of the brand’s original price, which is a 27% drop from the second generic’s level. This happens because with three or more manufacturers, no single company can control the market. Each must price aggressively to win business. The effect is strongest in high-volume drugs-those taken by more than 15,000 people monthly-where competition is fiercest.

Why do some generic drugs cost more even with multiple makers?

It’s usually because there aren’t actually multiple makers. Many markets are stuck in a duopoly-only two companies make the drug. A 2017 study found nearly half of all generic markets operate this way. When one company leaves, prices can spike 100-300%. Other reasons include complex manufacturing (like injectables), supply chain issues, or anti-competitive practices like patent thickets or pay-for-delay deals that block new entrants.

Do pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) pass on savings from generic competition?

Sometimes, but not always. PBMs negotiate discounts with manufacturers, and those discounts are bigger when more generics are available. But they don’t always pass the full savings to patients. Wholesaler markups and administrative fees eat into the difference. FDA data shows manufacturer prices drop 60-70% with multiple generics, but pharmacy acquisition costs only drop 40-50%. The rest goes to middlemen. Patients often pay based on the pharmacy’s retail price, not the true cost.

What’s being done to increase generic competition?

The FDA’s GDUFA III program (2023-2027) speeds up approvals for complex generics. Congress passed the CREATES Act to stop brand companies from blocking sample access. The Preserve Access to Affordable Generics Act targets pay-for-delay deals. But enforcement is inconsistent. More funding and faster review times are still needed, especially for drugs where only one or two companies make the generic.

Can I check how many generic makers are available for my drug?

Yes. Use GoodRx, Drugs.com, or your pharmacy’s price checker. These tools list all available generic versions and their prices. If you see only one or two options, ask your pharmacist if others could be ordered. Sometimes, a different manufacturer is available but not stocked. You might save 50% or more by switching.

Emily P

December 20, 2025 AT 03:47I’ve been on a generic statin for years and never realized how much the third maker dropped the price. My copay went from $45 to $12 last year-no joke. I just assumed pharmacies were being nice.

Vicki Belcher

December 21, 2025 AT 00:59THIS. 🙌 I was crying in the pharmacy aisle last week when I saw my insulin generic was $38 instead of $180. The third maker saved my life. We need MORE of these companies, not fewer. 💪❤️

Jedidiah Massey

December 21, 2025 AT 06:48It’s a textbook case of Bertrand competition dynamics in pharmaceutical oligopolies. The marginal cost of production for generics is near-zero post-FDA approval, so price elasticity becomes hyper-sensitive with >2 entrants. The kinked demand curve collapses under multi-firm pressure-hence the non-linear price decay. The FDA’s GDUFA III is essentially a regulatory nudge toward market efficiency.

Kitt Eliz

December 21, 2025 AT 08:04YESSSSS! 🚀 I work in health policy and this is the ONE thing we never talk about enough. More generics = lower premiums = lower insurance rates. It’s not magic, it’s math. If your PBM isn’t passing on the savings, switch plans. Demand transparency. Fight for your right to affordable meds. 💥

pascal pantel

December 21, 2025 AT 09:28Look, the whole ‘third generic drops prices’ thing is just a myth pushed by the FDA to make themselves look good. Most of those numbers are cherry-picked from high-volume drugs. For 80% of generics, there’s still only one or two players. And PBMs? They’re the real villains. Stop blaming pharma and start blaming the middlemen who pocket the difference.

Sahil jassy

December 22, 2025 AT 17:24Nicole Rutherford

December 22, 2025 AT 18:32Oh please. You think this is about patients? It’s about market share. The ‘savings’ are a distraction. The real story is how PBMs and wholesalers rig the system to keep profits high. And don’t even get me started on how the FDA approves generics with sketchy quality control just to hit quotas.

Mark Able

December 22, 2025 AT 19:40Wait, so you’re saying if I ask my pharmacist for a different generic, I could save hundreds? Why didn’t anyone tell me this before? I’ve been paying $120 for my thyroid med for years. I’m going to go right now. Thanks, stranger on the internet!

Chris Clark

December 23, 2025 AT 23:05Yo I’m from India and we got generics for pennies. Like, $2 for a month’s supply of metformin. But here? Even with three makers, pharmacies still charge $50 because the system’s broken. We need to copy India’s model. No middlemen. Just direct from factory to pharmacy. Simple.

Dorine Anthony

December 25, 2025 AT 07:16I just read this and felt a little less angry about my prescription bills. Thanks for laying it out so clearly. I didn’t know the third maker made that big a difference. I’ll start asking next time.

William Storrs

December 26, 2025 AT 03:56You’ve got this. Every time you ask your pharmacist if there’s another generic, you’re pushing the system to be fairer. Small actions add up. Keep speaking up-you’re not just saving money, you’re helping others too.

Alisa Silvia Bila

December 26, 2025 AT 10:55Third generic = $42 pill. That’s insane. And yet, I still pay $60 at my local CVS. Someone’s making a killing. Not me.

Marsha Jentzsch

December 27, 2025 AT 16:11THIS IS A SCAM!!! The FDA is in bed with Big Pharma!!! They approve generics just to make it look like competition exists-BUT THEY ALL OWN THE SAME STOCK!!! I saw a documentary-there’s a secret network of PBMs and CEOs who all live in the same gated community in Connecticut!!! They’re laughing at us while we pay $80 for a $3 pill!!!

Janelle Moore

December 28, 2025 AT 00:45So… are you saying the government is letting companies make fake pills? I think the FDA is lying to us. My cousin’s brother’s neighbor got sick from a generic. It was all a cover-up. They’re selling poison to save money. We need to boycott all generics now.

Henry Marcus

December 29, 2025 AT 17:51They call it a ‘generic’-but it’s really just a carbon copy with a different label. The brand-name company still owns the patent through shell corporations. The FDA? A puppet. The real drug? Made in China. The real price drop? A lie. You think you’re saving money? You’re just funding a global pharma cartel with better marketing.