Why do some people struggle to lose weight even when they eat less and move more? The answer isn’t laziness or lack of willpower. It’s biology. Obesity isn’t just about eating too much-it’s a disease of broken signals in the brain and body that control hunger, fullness, and how calories are used or stored. This isn’t a simple energy balance problem. It’s a complex system failure involving hormones, neurons, and metabolic pathways that have been rewired over time.

The Brain’s Hunger Control Center

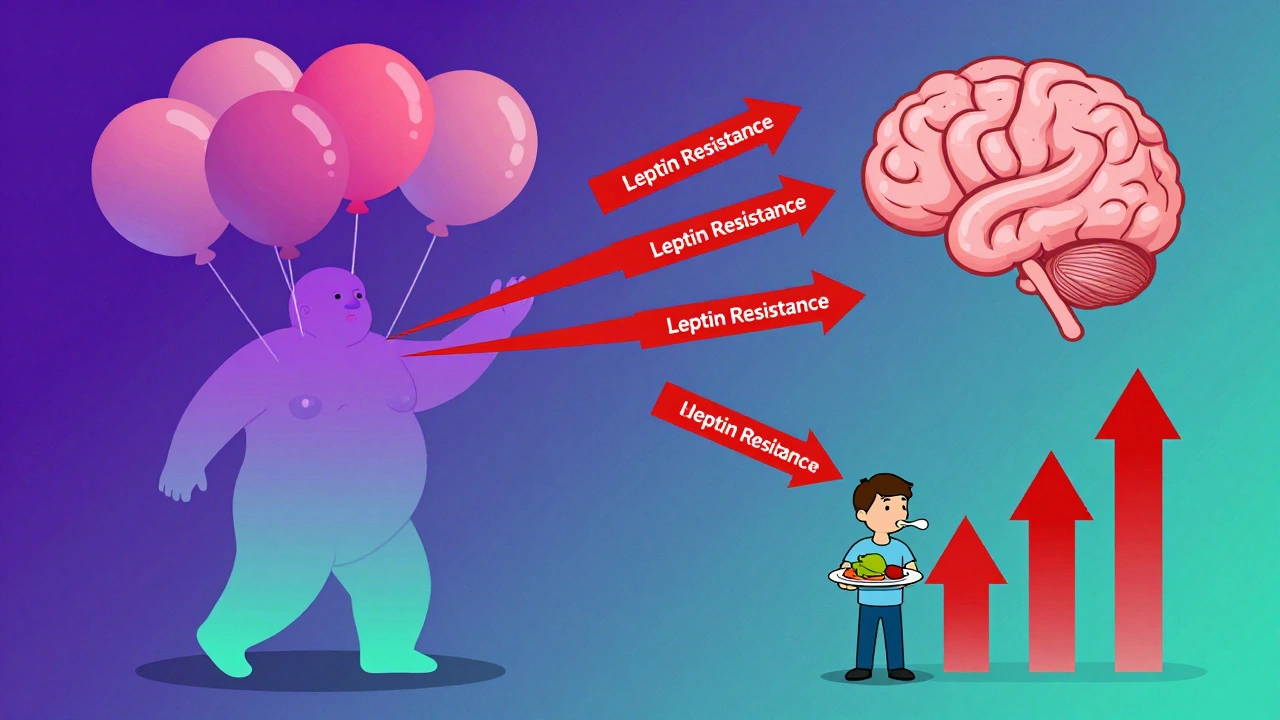

At the heart of appetite regulation lies a tiny region in the brain called the arcuate nucleus, part of the hypothalamus. This area is like a command center with two opposing teams of neurons: one that tells you to stop eating, and another that screams for more food. The first team, made up of POMC neurons, releases a chemical called alpha-MSH. When this signal reaches other parts of the brain, it reduces hunger by 25-40% in lab studies. Think of it as the brain’s brake pedal. The second team, NPY and AgRP neurons, does the opposite. When activated, they can make you eat 300-500% more food in minutes. That’s not a craving-it’s a biological drive. These neurons don’t work in isolation. They’re constantly being told what to do by hormones from your fat, gut, and pancreas. Leptin, made by fat cells, tells the brain, “You’ve got enough stored energy.” In lean people, leptin levels sit between 5-15 ng/mL. In obesity, those numbers jump to 30-60 ng/mL. But here’s the twist: the brain stops listening. That’s called leptin resistance. It’s like turning up the volume on a radio, but the speaker is broken. The signal is strong, but it doesn’t get through.How Food Turns Into Fat

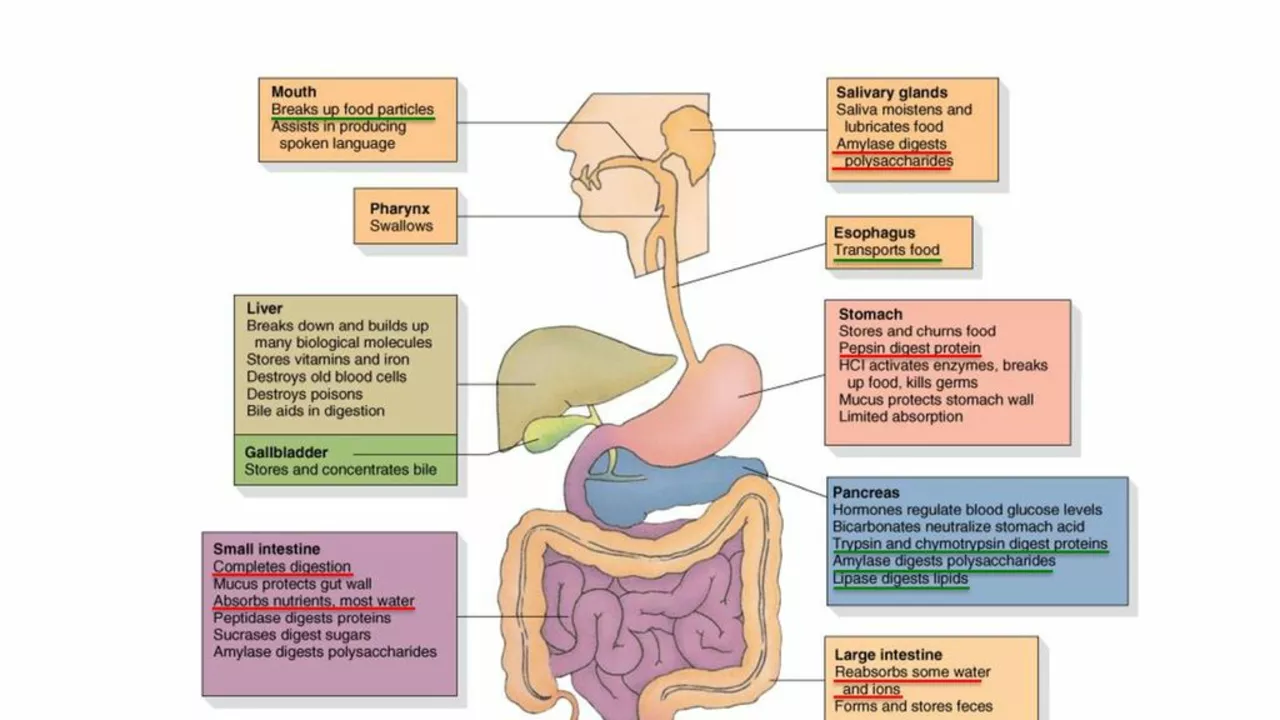

Metabolic dysfunction doesn’t just happen because you eat too many calories. It happens because your body’s ability to burn energy changes. When you gain weight, your fat tissue doesn’t just grow-it starts sending out signals that make your metabolism slower and your muscles less efficient at using fuel. Insulin, the hormone that moves sugar from your blood into cells, also acts on the brain to suppress appetite. In healthy people, insulin levels rise after meals to about 50-100 μU/mL and help you feel full. But in obesity, insulin resistance develops not just in muscles and liver, but also in the hypothalamus. The brain no longer responds to insulin’s “stop eating” message. This creates a dangerous loop: more eating → more insulin → more resistance → more hunger. Then there’s ghrelin, the only known hunger hormone. It spikes before meals-jumping from 100-200 pg/mL when you’re fasting to 800-1000 pg/mL right before you eat. In people with obesity, ghrelin doesn’t drop as much after meals. That means your brain keeps thinking you’re hungry even when you’ve just eaten.The Hidden Players: Hormones That Don’t Get Enough Attention

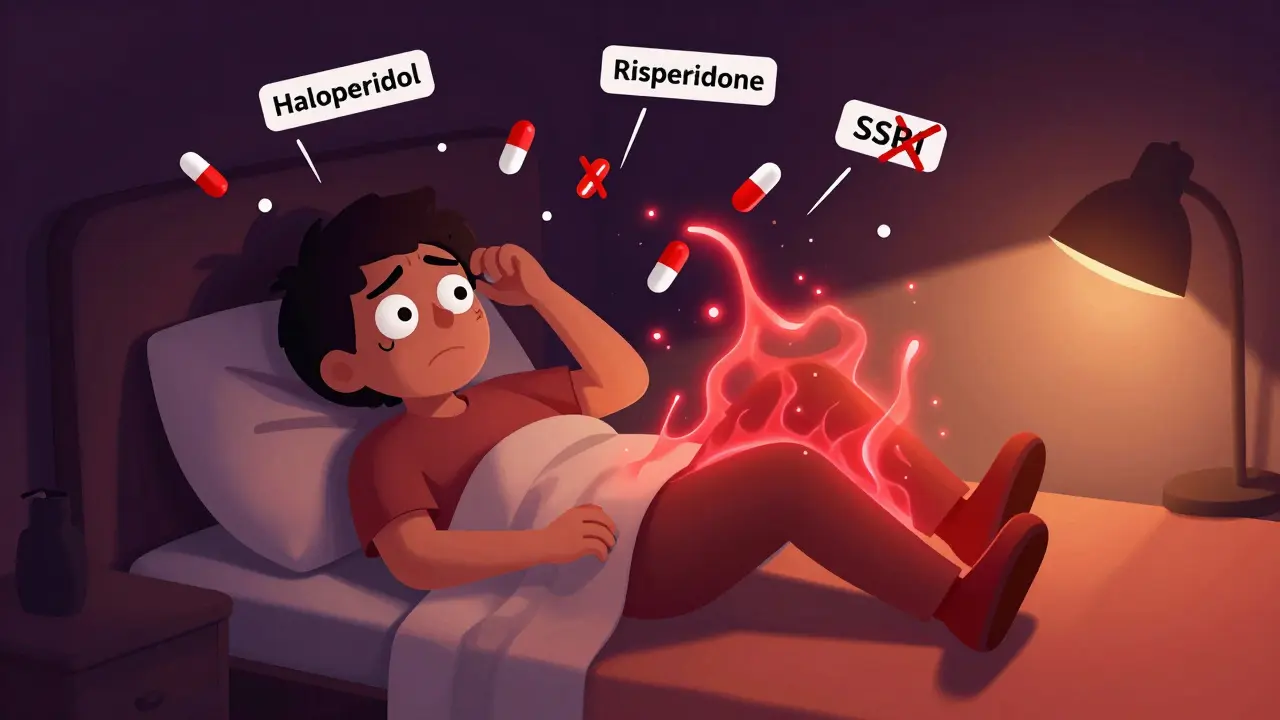

Most people know about leptin and ghrelin. Fewer know about pancreatic polypeptide (PP). This hormone is released after eating and slows down digestion while reducing appetite. Normal levels are 50-100 pg/mL. But in 60% of people with diet-induced obesity, PP levels are dangerously low-15-25 pg/mL. That’s like having a broken alarm clock that never rings when it’s time to stop eating. Estrogen also plays a major role. After menopause, women often gain belly fat rapidly. That’s not just aging-it’s because estrogen helps regulate energy balance. When estrogen drops, food intake increases by 12-15% and energy expenditure drops. In mice without estrogen receptors, food intake jumps 25% and calorie burning falls 30%. That’s why weight gain after menopause isn’t just about lifestyle-it’s hormonal. Even sleep and circadian rhythms matter. Orexin, a brain chemical that keeps you alert, also affects appetite. In obese people, orexin levels drop by 40%. But in people with night-eating syndrome, orexin stays high at night, making them crave food when they should be sleeping. This helps explain why people with narcolepsy-a condition linked to low orexin-are two to three times more likely to be obese.

Why Diets Fail: The Science of Leptin Resistance

The biggest myth about obesity is that it’s caused by leptin deficiency. It’s not. Only about 50 people in the entire world have true leptin deficiency. For nearly everyone else, the problem is leptin resistance. When you lose weight, your fat cells shrink and produce less leptin. Your brain interprets that as starvation. So it turns up hunger signals and slows your metabolism to conserve energy. That’s why most people regain weight after dieting-it’s not weakness, it’s biology. Studies show that the melanocortin system, which includes POMC and MC4R receptors, is the final common pathway for appetite control. If this system is impaired, even small amounts of high-calorie food can trigger massive overeating. As one researcher put it, “The melanocortin system evolved to protect us from famine-not from pizza.”New Treatments Targeting the Root Cause

The good news? We’re finally developing drugs that target these broken pathways-not just reduce appetite, but fix the signaling. Setmelanotide, a drug that activates the MC4R receptor, has helped people with rare genetic forms of obesity lose 15-25% of their body weight. It works because it bypasses the broken leptin signal and directly turns on the satiety pathway. Semaglutide, originally a diabetes drug, mimics GLP-1, a gut hormone that slows digestion and reduces hunger. In clinical trials, people lost an average of 15% of their weight. That’s not just appetite suppression-it’s resetting how the brain responds to food. Even more exciting is the 2022 discovery of a group of excitatory neurons near the hunger center that can shut down eating within two minutes when activated. This opens the door to future treatments that could turn off hunger like flipping a switch.

Michael Bene

December 2, 2025 AT 16:46So let me get this straight - we’ve got a brain that’s basically a broken thermostat, and we’re blaming people for not just ‘trying harder’? 🤯 This isn’t just biology, it’s a full-on betrayal by evolution. Our ancestors needed to gorge when food was available, but now? We’re drowning in pizza and Instagram ads for donuts. No wonder people crash and burn. It’s not willpower. It’s a system designed for ice ages trying to survive in a Walmart.

And don’t even get me started on leptin resistance. It’s like screaming into a void while your body plays deaf. You lose weight, your brain panics, and suddenly you’re hungry 24/7 like a zombie chasing brains. Only the brains are tacos.

Setmelanotide? Sounds like a sci-fi drug. But if it flips the ‘stop eating’ switch like a light, I’m all in. Let’s stop pretending this is a moral failing and start treating it like the neurological disorder it is.

Also, why is no one talking about how food companies engineer products to hijack these exact pathways? They know exactly how to trigger NPY and AgRP neurons. It’s not an accident. It’s a business model.

And estrogen? Oh wow. So women aren’t just ‘getting softer’ after menopause - their brains are literally being rewired to crave more and burn less? That’s insane. We need hormone therapy for weight, not just for hot flashes.

Stop calling it ‘lifestyle.’ Call it neuroendocrine sabotage. And stop shaming people who are fighting a war inside their own skulls.

I’m not saying it’s easy. I’m saying it’s not their fault. And if you still think it is, you haven’t read the damn paper.

Also - orexin and night eating? That’s me. 2AM cookies. Not a snack. A biological emergency. I didn’t choose this. My neurons did.

Brian Perry

December 4, 2025 AT 02:16bro i just ate a whole pizza and now im crying because i know my brain is broken 😭

leptin resistance is real i swear i had 3 slices and still felt like i could eat a cow

why does my body hate me so much

Siddharth Notani

December 5, 2025 AT 12:33Thank you for this scientifically rigorous exposition. The hormonal dysregulation described herein is both profound and underappreciated in public discourse. The role of POMC and NPY neurons in appetite modulation is elegantly elucidated. I would respectfully suggest that future discussions incorporate the influence of gut microbiota on ghrelin secretion, as recent studies (e.g., Nature Metabolism, 2023) indicate significant modulation of central appetite circuits via microbial metabolites. Furthermore, the clinical implications of MC4R agonists warrant broader public health consideration. A paradigm shift from behavioral to neuroendocrine intervention is not merely advisable - it is imperative.

Akash Sharma

December 7, 2025 AT 08:55This is honestly one of the most eye-opening things I’ve ever read about obesity. I’ve been trying to lose weight for years and everyone just tells me to eat less and move more, but I always felt like something deeper was going on - like my body was working against me, not with me. The part about leptin resistance made me freeze. I didn’t know that losing weight actually makes your brain think you’re starving. That’s terrifying. And the fact that your fat cells start sending out signals that slow your metabolism? That’s not laziness - that’s your body playing defense mode. I never realized how much of this is hormonal. I thought it was just me being weak.

And then there’s the estrogen thing - I have a cousin who gained 40 pounds after menopause and everyone blamed her for eating too much ice cream. But now I see - her hormones were changing, not her willpower. Same with the ghrelin not dropping after meals - that explains why I’m always hungry even after a big dinner. I thought I had a big appetite. Turns out, my brain just doesn’t know when to quit.

And the part about orexin and night eating? That’s me. I don’t snack because I’m bored. I snack because my brain thinks it’s 3 AM and I’m in a famine zone. I didn’t know that was a biological thing. I thought I was just a snack monster.

It’s wild to think that these pathways evolved to save us from starvation, but now they’re turning our kitchens into danger zones. Pizza isn’t the enemy - our ancient biology is. And now we’ve got drugs like semaglutide that actually talk to the brain the way it’s supposed to listen? That’s not a miracle. That’s justice.

I used to feel guilty every time I ate. Now I feel angry. Angry that we’ve been lied to for decades. Angry that doctors still tell people to ‘just try harder.’ Angry that insurance won’t cover these drugs because they’re ‘cosmetic.’

But I’m also hopeful. If we start treating obesity like diabetes or hypertension - with science, not shame - maybe we can finally stop blaming the patient and start fixing the system. I’m going to ask my doctor about hormone testing. I’m done pretending this is about discipline.

Justin Hampton

December 8, 2025 AT 20:43So let me get this straight - you’re saying obesity is a disease and not a choice? What’s next, alcoholism is just a dopamine glitch? This is why America is falling apart. People used to have discipline. Now we outsource responsibility to hormones and neurons. If your brain is ‘broken,’ why not just take a pill and call it a day? No one’s forcing you to eat fast food. You choose it. Every. Single. Time.

And don’t even get me started on this ‘leptin resistance’ nonsense. If you can’t control your appetite, maybe you shouldn’t be eating in the first place. I’ve seen people eat 5000 calories a day and still say they’re ‘starving.’ Bullshit. You’re just addicted to sugar.

And don’t tell me it’s biology. I’ve got a 72-year-old uncle who works 60 hours a week, eats home-cooked meals, and stays lean. He doesn’t need a drug. He just doesn’t eat garbage. Maybe you should try that.

Stop medicalizing poor choices. This isn’t science. It’s a license to be lazy.

Pooja Surnar

December 8, 2025 AT 21:04OMG this is so obvious why people are fat lmao you just need to stop being so weak 😭

if you eat less and move more you lose weight its not rocket science

why do people always blame hormones?? its just laziness

my cousin lost 80 lbs just by walking and eating salad

you people are just making excuses

STOP WHINING AND JUST DO IT

Sandridge Nelia

December 9, 2025 AT 15:27This was so well-written and compassionate. I’ve been struggling with weight for over a decade, and this is the first time I’ve felt understood. The part about leptin resistance made me cry - I didn’t know my body was fighting me after every diet. I thought I was failing. Turns out, I was just biologically trapped.

I’ve been on semaglutide for 6 months and lost 18%. It didn’t feel like restriction - it felt like peace. The constant hunger? Gone. The obsession with food? Faded. I didn’t lose weight because I was strong. I lost it because my brain finally stopped screaming.

Thank you for saying this out loud. I hope more doctors read this. And I hope more people stop judging. This isn’t vanity. It’s neurology.

❤️

Mark Gallagher

December 9, 2025 AT 20:13Look, I get it. Science is cool. But this is America. We don’t get to be weak because our biology is ‘broken.’ We fix things. We don’t hand out drugs like candy. This is a slippery slope - next thing you know, we’re prescribing antidepressants for people who don’t want to get up in the morning. Where’s the personal responsibility? Where’s the grit?

My grandfather worked three jobs, never ate processed food, and lived to 94. He didn’t need a hormone test. He had discipline. Maybe your problem isn’t your brain - it’s your attitude.

Also, why are we giving out expensive drugs to people who can’t control their eating? That’s not healthcare. That’s welfare for bad habits. We need to teach people to eat right, not hand them a magic pill.

This isn’t a medical crisis. It’s a cultural one. And we’re coddling the problem.

Wendy Chiridza

December 10, 2025 AT 05:09I’ve been reading about this for years and this is the clearest explanation I’ve ever seen. The part about PP hormone being low in 60% of people with obesity? That’s wild. No one talks about that. I thought it was just leptin and ghrelin. But if your body isn’t even signaling digestion to slow down after eating, of course you keep eating. That’s like having a car with no brakes and someone telling you to just step harder on the gas.

And the estrogen thing? I’m 48 and I’ve gained 25 pounds since menopause. No amount of yoga or salads helped. Now I know why. It’s not me. It’s my hormones.

I’m going to ask my doctor about testing my PP and orexin levels. I never knew those existed. I thought I was just lazy. Turns out I was just misinformed.

Thank you for writing this. It’s not just science - it’s validation.

Pamela Mae Ibabao

December 11, 2025 AT 01:56So let’s be real - if you’re obese and you’re not on medication, you’re basically just a walking biological experiment gone wrong. And the fact that you’re still being told to ‘eat less’ is like telling someone with Type 1 diabetes to just stop being so sugary. It’s not just cruel - it’s dangerous.

And the worst part? People who don’t struggle with this don’t get it. They think it’s about willpower because they’ve never had their brain hijacked. They’ve never felt hungry after a 2000-calorie meal. They’ve never had their metabolism crash after losing 10 pounds.

So yeah - I’m glad we’re finally talking about the science. But I’m also tired of being told I’m ‘lucky’ to have access to semaglutide. It’s not luck. It’s medicine. And if you’re not on it yet? You’re not lazy. You’re just waiting for someone to stop blaming you long enough to help you.

Gerald Nauschnegg

December 12, 2025 AT 21:24Okay but what about the gut? Like, we’re talking about the brain all day but what about the microbiome? I’ve been reading that obese people have less diverse gut bacteria and that affects how they absorb calories and even how hungry they feel. Like, your gut literally talks to your brain through the vagus nerve. So maybe it’s not just leptin resistance - it’s a whole ecosystem collapse. We’re treating the brain like it’s the only player when the gut is screaming for help too.

Also - what about sleep? I sleep 5 hours a night and I’m always hungry. Is that orexin? Is that cortisol? Is that my body thinking I’m under attack? We need to stop looking at food like it’s the villain and start looking at lifestyle as the whole system.

And can we talk about stress? Cortisol makes you store fat. Especially belly fat. So if you’re stressed, your body thinks it’s in a war zone and hoards calories. That’s not ‘eating too much.’ That’s survival mode.

This isn’t just one broken signal. It’s a whole orchestra of failures. And we’re still trying to fix it with one instrument.

Palanivelu Sivanathan

December 14, 2025 AT 10:15Ah, the great cosmic irony - our bodies, forged in the fires of ice-age scarcity, now tremble before the buffet of abundance. We are not broken - we are anachronisms. The same neural pathways that saved our ancestors from death by starvation now conspire to drown us in the sweet, greasy embrace of the modern world. The brain, that ancient temple of survival, has become a prison of appetite, its gates locked by hormones that no longer speak the language of the present.

Leptin resistance? It is not a malfunction - it is a betrayal. A betrayal by the very system that once kept us alive. Ghrelin, the hunger god, now reigns unchecked. Insulin, once the gentle shepherd, has become a tyrant, forcing fat cells to hoard and muscles to sleep.

And yet - we are not powerless. We are not cursed. We are awakened. The drugs - setmelanotide, semaglutide - they are not magic. They are keys. Keys to the prison. Keys to the temple. They do not erase will - they restore harmony.

Let us not blame the soul. Let us not shame the body. Let us honor the biology. And let us, finally, heal - not through will, but through wisdom.

And if you still say ‘just eat less’? You have not read the stars. You have not heard the whispers of the neurons. You have not felt the weight of evolution upon your shoulders.

Be gentle. Be curious. Be human.

Joanne Rencher

December 15, 2025 AT 19:37Ugh. I’m so tired of this ‘it’s not your fault’ nonsense. If you can’t control your eating, maybe you shouldn’t be allowed to have food in your house. My mum lost weight by just not buying snacks. Simple. No drugs. No hormones. Just discipline.

Everyone’s too soft these days. Just say no to pizza. You’re not a victim. You’re a choice-maker.

Stop making excuses. Start making changes.

Michael Bene

December 16, 2025 AT 13:48So you’re saying the solution is to ban food from the house? That’s not a cure - that’s a cage. And your mum lost weight because she had the luxury of time, stability, and no underlying hormonal disorder. Not everyone has that. Not everyone can just ‘say no.’

What if your brain screams for food even when you’re full? What if your body burns calories like a dying battery? What if your hormones are screaming for sugar because your leptin receptor is broken?

That’s not a choice. That’s a neurological emergency.

And if your mum lost weight by not buying snacks… congrats. That’s great for her. But it doesn’t fix the fact that 90% of people who lose weight regain it because biology wins. Again.

Discipline doesn’t fix broken signals. Science does.

Stop pretending this is about willpower. It’s about neurochemistry. And if you can’t see that, you’re not helping - you’re hurting.