Have you ever filled the same generic prescription in two different states and been shocked by the price difference? You might pay $12 for a 30-day supply of lisinopril in Ohio, then $48 for the exact same pill in California. It’s not a mistake. It’s not a glitch. It’s the system - and it’s designed this way.

Why the Same Pill Costs Twice as Much in One State

Generic drugs are supposed to be cheap. They’re copies of brand-name medicines, made after patents expire. They don’t need new clinical trials. They cost pennies to produce. Yet in some states, you’re paying five times more than you should. Why?The answer isn’t one thing. It’s a tangled web of pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs), state Medicaid rules, lack of transparency, and weak competition. PBMs act as middlemen between insurers, pharmacies, and drug manufacturers. They negotiate prices, manage formularies, and collect rebates. But their pricing models aren’t public. And what they charge your insurer isn’t what you pay at the counter.

In states like California and Vermont, laws require PBMs to disclose pricing practices. That transparency pushes prices down. In states with no such laws, PBMs can hide markups. You think your insurance is saving you money - but often, it’s the opposite. A 2022 USC Schaeffer Center study found that insured patients paid 13% to 20% more for generics than cash-paying customers. That’s because PBMs structure copays to maximize their own profits, not yours.

How Medicaid Shapes What You Pay

Medicaid, which covers over 80 million Americans, sets the baseline for many private insurance plans. Each state runs its own Medicaid program and picks how it reimburses pharmacies for generics. Some use the National Average Drug Acquisition Cost (NADAC), updated monthly. Others use outdated benchmarks or arbitrary formulas.States that update prices regularly and use real-time data pay pharmacies closer to what they actually pay for drugs. That keeps retail prices lower. States that lag behind? Pharmacies make up the difference by charging patients more - especially those without insurance or with high-deductible plans.

Take atorvastatin, the generic version of Lipitor. In 2022, GoodRx data showed prices ranging from $4 to $18 for a 30-day supply across different states. That’s not because the drug costs more to make in one place. It’s because one state’s Medicaid program reimburses pharmacies at 90% of the true cost, while another pays only 60%. The gap gets passed to you.

The PBM Black Box

PBMs are the hidden engine behind most price differences. They don’t just negotiate discounts - they collect secret rebates from drugmakers. Then they decide how much of that rebate gets passed on to you, your insurer, or their own profits.Here’s how it works: A drugmaker offers a $10 rebate per pill to a PBM. The PBM tells your insurer, “We saved you $10.” But your copay stays the same. Meanwhile, the PBM pockets the rebate - or uses it to inflate the list price so future rebates get bigger. This is called “spread pricing.” And it’s legal in most states.

States that ban spread pricing - like Minnesota and Maryland (before its law was struck down) - see lower out-of-pocket costs. But in states where it’s allowed, your $10 copay might cover a pill that cost the pharmacy $2. The PBM keeps the rest.

Why Cash Often Beats Insurance

If you’ve ever used GoodRx or Cost Plus Drug Company, you’ve seen this: Paying cash for a generic can save you 70%. Why? Because your insurance plan has a negotiated price - but it’s not the lowest price available.When you pay cash, you bypass the PBM entirely. You’re buying directly from the pharmacy at their wholesale cost, plus a small markup. In states with high PBM control, like New York or Florida, cash prices can be half of your insurance copay. In states with strong transparency laws, like Oregon or Washington, the gap is smaller - but still there.

Here’s the kicker: 97% of cash payments for prescriptions are for generics. That’s not because people are trying to be clever. It’s because the system is rigged. Insurance doesn’t always help - it often makes things worse.

Competition (or Lack of It)

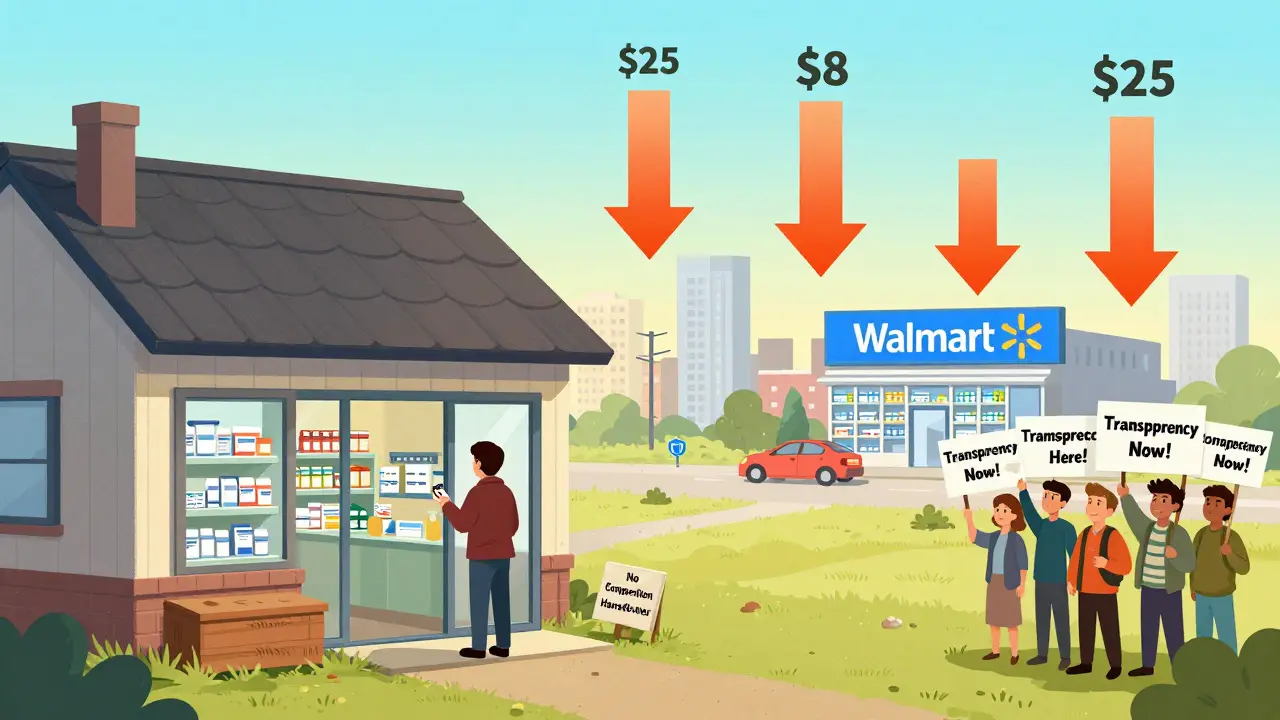

In rural areas, you might have one pharmacy within 50 miles. That pharmacy doesn’t have to compete on price. It can charge more because you have no choice. Urban areas with multiple chains - CVS, Walgreens, Walmart, independent pharmacies - see lower prices because competition forces them to be transparent.Walmart and Costco often sell common generics for $4 to $10 because they use volume to cut margins. But if you live in a town with only one pharmacy, that discount doesn’t exist. That’s why the same drug can cost $25 in a small town in Alabama and $8 in a big city in Colorado.

And it’s not just about location - it’s about market concentration. In states where one or two PBMs control 80% of the market, prices stay high. In states with more competition among PBMs, prices drop. But most consumers don’t know which PBMs their insurer uses - let alone how they operate.

State Laws: A Patchwork of Hope and Hurdles

Since 2016, over 100 state bills have tried to fix drug pricing. Some worked. Some got blocked.Vermont and California passed laws requiring PBMs to disclose pricing. Result? Patients in those states paid 8-12% less for generics than those in states without transparency rules.

Maryland tried to ban price gouging on generics. A federal court struck it down, saying states can’t interfere with interstate commerce. Nevada tried to cap diabetes drug prices. The lawsuit was dropped - not because it was weak, but because drugmakers threatened to sue under trade secrets law to block data release.

Today, 18 states have drug affordability review boards. These panels can investigate price spikes and recommend limits. But they can’t force manufacturers or PBMs to lower prices. They can only shine a light. And sometimes, that’s enough.

What the Inflation Reduction Act Did - and Didn’t Do

The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 capped insulin at $35 a month for Medicare patients. Starting in 2025, it will cap out-of-pocket drug costs at $2,000 a year - but only for Medicare Part D users.That’s good news for seniors. But it doesn’t help the 70% of Americans under 65 who get insurance through employers or buy plans on the marketplace. And it doesn’t touch PBM practices or state-level reimbursement rules.

Even for Medicare patients, savings vary by state. Why? Because Medicare Part D plans are run by private insurers, who use different PBMs in different states. So your $35 insulin cap might mean $35 in Texas, but $42 in Pennsylvania - because the PBM sets the list price higher and the cap just brings it down to $35.

What You Can Do Right Now

You can’t change state laws. But you can change how you pay.- Always check GoodRx or SingleCare before filling a prescription - even if you have insurance.

- Ask the pharmacist: “What’s your cash price?” Sometimes it’s lower than your copay.

- If you’re on Medicaid, find out what pricing benchmark your state uses. Call your state’s Medicaid office.

- Switch to a pharmacy that sells generics at cost - like Costco, Walmart, or Mark Cuban’s Cost Plus Drug Company.

- Join a patient advocacy group in your state pushing for PBM transparency laws.

There’s no single fix. But there’s a simple truth: You’re not powerless. The system is designed to make you feel like you have no control. But when you pay cash, you bypass the middlemen. And that’s where real savings begin.

What’s Next?

Experts predict state-level pricing differences will slowly narrow as more states adopt transparency laws and federal reforms take hold. But PBMs are powerful. They spend millions lobbying to keep their models secret.For now, the biggest driver of price variation isn’t the cost of the drug. It’s the cost of the system around it. And that system is still broken - in different ways, in every state.

Why is my generic drug more expensive in one state than another?

Generic drug prices vary by state because of differences in state Medicaid reimbursement rates, Pharmacy Benefit Manager (PBM) practices, pharmacy competition, and transparency laws. States with strong disclosure rules, like California and Vermont, tend to have lower prices. States with weak oversight and concentrated PBM markets often have higher prices due to hidden markups and spread pricing.

Should I use my insurance or pay cash for generic drugs?

For most generics, paying cash - especially through services like GoodRx or at Walmart or Costco - is often cheaper than using insurance. This is because insurance copays are set by PBMs to maximize their profits, not yours. Always ask the pharmacy for the cash price before swiping your card.

Do state laws actually lower generic drug prices?

Yes - but only if they require transparency. States that force PBMs to disclose pricing and ban spread pricing have seen 8-12% lower out-of-pocket costs for generics. Laws that try to cap prices directly, like Maryland’s, have been blocked in court. The most effective laws don’t set prices - they shine a light on them.

Why are rural pharmacies more expensive for generics?

Rural areas often have only one pharmacy, so there’s no competition to drive prices down. Pharmacies in these areas don’t have the volume to negotiate lower wholesale prices, and they can’t absorb the cost of selling generics at a loss. That’s why the same drug can cost twice as much in a small town as in a big city.

Will the Inflation Reduction Act fix state-level price differences?

Not directly. The Inflation Reduction Act only caps costs for Medicare Part D beneficiaries. It doesn’t regulate PBMs, change Medicaid reimbursement, or require price transparency for non-Medicare patients. So while it helps seniors, most Americans will still face wide price gaps between states unless their state passes its own transparency laws.

Kimberly Reker

January 30, 2026 AT 01:03Just paid $18 for metformin at my local pharmacy. Checked GoodRx - $6. Cash. No insurance needed. I feel like I’ve been scammed for years.

Why do we even have insurance if it doesn’t save us money on generics?

Rob Webber

January 30, 2026 AT 08:51This whole system is a scam engineered by PBMs and pharma lobbyists. They don’t care if you go bankrupt. They care about quarterly profits. And the government lets them get away with it because they fund every damn campaign.

It’s not broken - it’s working exactly as designed.

Lisa McCluskey

January 30, 2026 AT 15:42I used to think my insurance was helping until I started comparing cash prices.

Turns out I was paying double for the same pill.

Now I always ask the pharmacist first. Simple habit. Big savings.

owori patrick

January 30, 2026 AT 19:13Same thing happens in Nigeria with some meds. Local pharmacies charge more because they import through middlemen. No transparency. No competition.

It’s not just America. This is global.

Claire Wiltshire

January 31, 2026 AT 15:56If you’re on a high deductible plan or uninsured, paying cash through GoodRx or Costco is almost always the smarter move.

It’s not a hack. It’s basic financial literacy.

Pharmacies aren’t hiding the cash price - you just have to ask.

Darren Gormley

February 1, 2026 AT 04:39Everyone’s acting like this is new. 🤡

PBMs have been doing this since the 90s.

And now you’re surprised?

Also - Walmart’s $4 generics? They’re losing money on them. It’s a loss leader. You think they care about you? They care about foot traffic.

Stop romanticizing big box stores.

Mike Rose

February 2, 2026 AT 03:13bro why is a pill so expensive??

like its not even a phone or a car

its just a tiny white thing

why am i paying 50 bucks for it

rip

Russ Kelemen

February 2, 2026 AT 13:00This isn’t just about drug prices.

It’s about who we let control our health.

We outsourced pricing to faceless corporations that answer to shareholders, not patients.

And now we’re shocked when they choose profit over people?

We built this. We let them.

Change starts when we stop treating healthcare like a commodity and start treating it like a right.

Not a privilege.

Not a negotiation.

A right.

Sidhanth SY

February 3, 2026 AT 05:00India makes 80% of the world’s generic drugs.

Yet here we are paying 10x more because of middlemen.

Imagine if we cut out the PBMs and imported directly.

Cost would drop to $1 a pill.

But no one wants to disrupt the gravy train.

Sarah Blevins

February 3, 2026 AT 14:45There is no systemic issue here. Price variation reflects local market dynamics, including labor costs, rent, and regulatory overhead.

Comparing a rural pharmacy in Alabama to a Walmart in Colorado is not a fair comparison.

It is anecdotal and misleading.

Beth Cooper

February 3, 2026 AT 19:04Did you know the FDA is in on it?

They approve the generics but let PBMs control the pricing.

And the real secret? The same pills are often made in the same factory.

They just put different labels on them.

One goes to Walmart. One goes to your insurance pharmacy.

Same pill. Different price.

It’s a scam. A giant, legal, multi-billion dollar scam.

Donna Fleetwood

February 5, 2026 AT 04:10Just told my mom to use GoodRx for her blood pressure med.

She went from $47 to $7.

She cried.

Not from sadness.

From relief.

That’s the power of knowing your options.

You’re not helpless.

Start small. Ask the pharmacist.

It changes everything.

Melissa Cogswell

February 5, 2026 AT 18:07I work at a small pharmacy in rural Ohio.

We don’t make money on generics.

We lose money on them.

But we sell them anyway because someone’s life depends on it.

So when you say ‘just pay cash’ - you don’t know how hard that is for us too.

We need real reform. Not just individual hacks.