When a teenager is struggling with deep sadness, loss of interest in everything, or thoughts of not wanting to live, parents and doctors face a terrifying choice: start an antidepressant, or wait? The decision is made harder by a warning stamped in bold black letters on every prescription bottle - the FDA’s black box warning. It says antidepressants may increase the risk of suicidal thoughts in kids and teens. But here’s the thing: that same warning might be keeping teens from getting help they desperately need.

What the Black Box Warning Actually Says

In October 2004, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) added a black box warning - the strongest safety alert they have - to all antidepressant labels. It wasn’t about side effects like weight gain or nausea. It was about suicide risk. The warning came after a review of 24 clinical trials involving over 4,400 children and teens with depression or OCD. In those studies, 4% of kids on antidepressants showed signs of suicidal thinking or behavior. That’s twice the rate of kids on placebo (2%). No one died in those trials. But the pattern was clear enough for the FDA to act. The warning was expanded in 2007 to include young adults up to age 24. It applies to every antidepressant - whether it’s fluoxetine (Prozac), sertraline (Zoloft), venlafaxine (Effexor), or bupropion (Wellbutrin). The label doesn’t say antidepressants cause suicide. It says they may increase the risk of suicidal thoughts or actions, especially in the first few weeks of treatment or after a dose change. The FDA also required every pharmacy to hand out a Patient Medication Guide with every new prescription. It tells families: watch for new or worsening depression, anxiety, panic attacks, irritability, agitation, or any unusual behavior. If you see these signs, call the doctor right away.The Unintended Consequences

Here’s where things get complicated. After the warning went out, prescriptions for antidepressants in teens dropped by more than 22% between 2004 and 2006. That sounds like a win - fewer kids on meds. But what happened next? Suicide rates among 10- to 19-year-olds rose by nearly 18% over the next four years, according to CDC data. Psychotropic drug poisonings - a common measure of suicide attempts - jumped 22%. A major 2023 study in Health Affairs looked at 11 high-quality studies and found a direct link: fewer antidepressant prescriptions meant more suicide attempts and deaths. The researchers didn’t say antidepressants prevent suicide. They said not treating depression leads to worse outcomes. In one case, a teen with severe depression refused medication because of the warning. A year later, they attempted suicide. Their doctor said: if they’d started treatment earlier, the outcome might have been different. The American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP) admitted in 2007 that the warning had created a climate of fear. Parents now hesitate. Some doctors delay starting meds, waiting for families to “get comfortable.” One survey of 500 child psychiatrists found 76% reported treatment delays of over three weeks - just because of the warning.Does the Warning Actually Improve Monitoring?

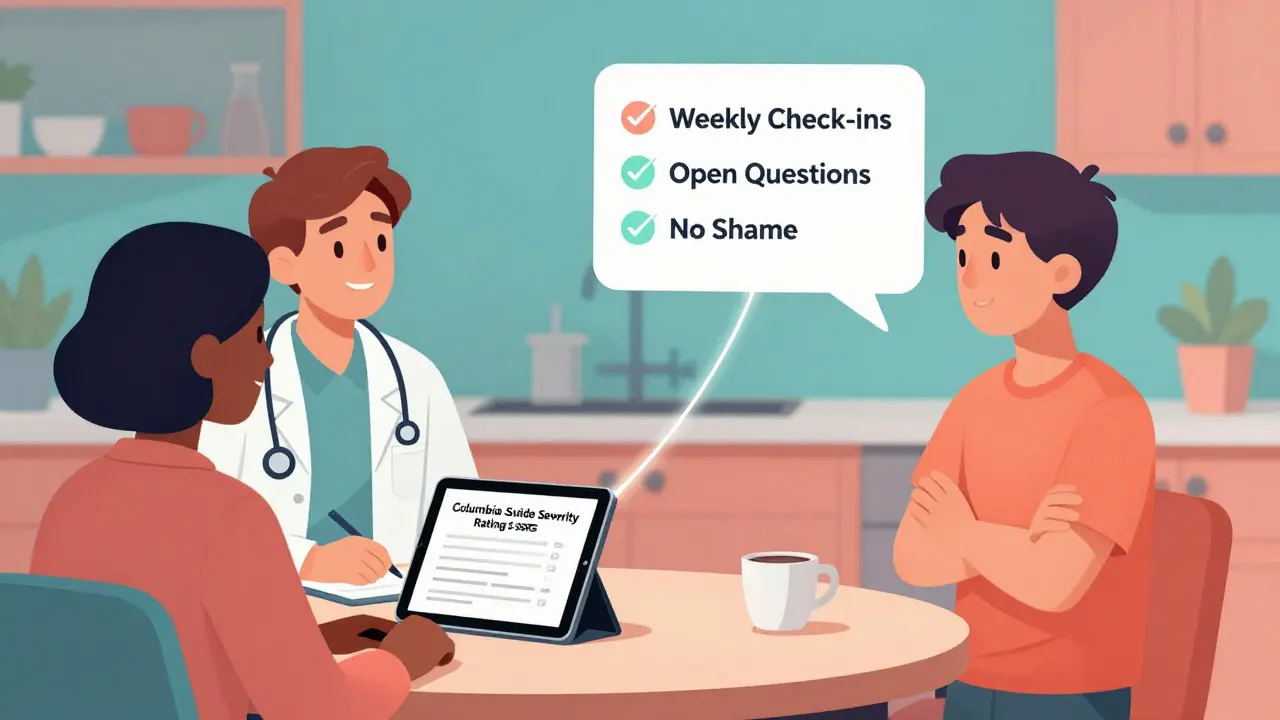

The FDA’s goal was to make doctors pay closer attention. But here’s the surprise: the one study that actually measured whether doctors started checking more often for suicidal thoughts found no increase. Instead, doctors spent more time explaining the warning to worried parents. They spent less time doing the real work: assessing symptoms, adjusting doses, or building trust. The recommended monitoring protocol is simple: weekly check-ins for the first month, then every two weeks for the second month, then monthly. Use tools like the Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS) to ask direct questions: “Have you had thoughts of hurting yourself?” “Do you have a plan?” “Do you have access to means?” But in real life? Many clinics don’t have the staff or time. School counselors don’t get training. Parents don’t know what to look for. And teens? They often hide what they’re feeling - even from their own parents.

What Does the Evidence Really Show?

Critics of the warning point out that the original data came from short-term trials - usually 8 to 12 weeks. These weren’t real-world settings. Patients in trials are carefully selected. Many have mild symptoms. They’re not the ones most at risk. A 2023 Cochrane review of 34 trials with over 6,700 teens found the evidence on suicide risk was “low to very low quality.” Why? Because suicidal events were rare. The numbers were too small to draw firm conclusions. Some studies didn’t even report suicidality properly. Meanwhile, other research shows antidepressants can work. A Mayo Clinic survey of 1,200 teens on SSRIs found 87% improved without any suicidal thoughts. Of the 3% who did have transient suicidal ideas, those thoughts went away after a dose adjustment or added therapy. And here’s the most telling data: in countries where antidepressant use didn’t drop after the warning - like the UK and Australia - teen suicide rates didn’t spike. In fact, in places where treatment rates stayed stable or rose, suicide rates fell.Who Benefits From the Warning? Who Gets Hurt?

The warning was meant to protect. But the people most at risk - teens with severe depression, those with a history of self-harm, those without access to therapy - are the ones now least likely to get help. The American Psychiatric Association and AACAP both agree: for teens with moderate to severe depression, the benefits of antidepressants outweigh the risks. Fluoxetine (Prozac) is the only SSRI with strong evidence of effectiveness in teens. Sertraline and escitalopram also have good data. Bupropion and mirtazapine are used off-label with caution. The problem isn’t the drugs. It’s the fear. And the lack of support.What Should Parents and Doctors Do?

If your teen is being treated for depression, here’s what works:- Start with therapy. CBT or interpersonal therapy (IPT) should be the first step. Medication isn’t always needed.

- Choose fluoxetine. It’s the best-studied SSRI for teens. If a doctor suggests another, ask why.

- Start low, go slow. A low dose reduces side effects and helps spot early warning signs.

- Check in weekly. Ask directly: “Have you had any thoughts about not wanting to be alive?” Don’t avoid the question. It doesn’t put the idea in their head - it opens the door.

- Keep the lines open. Teens need to know they’re not alone. Keep talking. Even if they shut down, keep showing up.

- Don’t stop meds suddenly. Stopping antidepressants can cause withdrawal and worsen depression. Always taper under medical supervision.

The Bigger Picture

The black box warning was born from good intentions. But after 20 years, the data shows it’s causing more harm than good. More teens are dying because they’re not getting treated. More families are paralyzed by fear. More doctors are avoiding the conversation. The FDA’s Psychopharmacologic Drugs Advisory Committee is reviewing the warning in 2024. Experts are calling for a change - not removal, but revision. Replace the black box with a clear, balanced warning: “Antidepressants can help treat depression in teens. In the first weeks of treatment, some may experience increased suicidal thoughts. Close monitoring reduces this risk. Untreated depression carries a higher risk of suicide.” The science is shifting. The fear hasn’t. We need to catch up.When to Seek Emergency Help

If your teen says they have a plan to end their life, has access to means (meds, weapons, etc.), or seems determined to act - call 988 (Suicide & Crisis Lifeline) or go to the nearest emergency room. Don’t wait. Don’t hope it’ll pass. This is a medical emergency.What Works Better Than Fear

The best protection isn’t a warning on a pill bottle. It’s a system: regular therapy, consistent medication management, family support, school awareness, and open communication. Antidepressants aren’t magic. But when used right - with care, monitoring, and compassion - they save lives.For teens drowning in depression, the right medication isn’t the enemy. Silence is.

Do antidepressants cause suicide in teens?

No, antidepressants don’t cause suicide. But in the first few weeks of treatment, some teens may experience increased suicidal thoughts - a known side effect. The risk is small (about 4% in clinical trials) and usually temporary. The bigger danger is leaving depression untreated, which carries a much higher risk of suicide. Antidepressants, especially fluoxetine, have been shown to reduce symptoms and improve functioning in teens with moderate to severe depression.

Why is there a black box warning if the risk is so low?

The warning was added in 2004 after a review of clinical trials showed a doubling of suicidal thoughts in teens on antidepressants compared to placebo. No suicides occurred in those studies, but the pattern was consistent across multiple drugs. The FDA acted to make sure doctors and families were aware. However, newer research shows the warning has led to fewer prescriptions and more suicide deaths - suggesting the unintended consequences may outweigh the benefits.

Which antidepressants are safest for teens?

Fluoxetine (Prozac) is the only SSRI with strong, consistent evidence of effectiveness and safety in teens. Sertraline (Zoloft) and escitalopram (Lexapro) are also commonly used and well-studied. Bupropion (Wellbutrin) and mirtazapine (Remeron) are sometimes prescribed off-label but have less data for adolescents. Always start with the lowest effective dose and monitor closely.

How often should a teen be monitored when starting antidepressants?

Guidelines recommend weekly check-ins for the first month, biweekly for the second month, and then monthly. Each visit should include a direct assessment using tools like the Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS). Parents should be involved, and communication with schools is helpful. Monitoring isn’t just about checking for suicide risk - it’s about tracking mood, sleep, energy, and side effects.

Should I avoid antidepressants for my teen because of the warning?

No - unless your teen has very mild symptoms and is responding well to therapy alone. For moderate to severe depression, the risks of not treating - including academic decline, social isolation, self-harm, and suicide - are far greater than the small, manageable risk of increased suicidal thoughts. The warning should guide monitoring, not block treatment. Work with a child psychiatrist to make an informed decision.

Can therapy replace antidepressants for teens?

For mild depression, therapy alone - especially CBT or IPT - can be very effective. For moderate to severe depression, combining therapy with medication works better than either alone. Antidepressants help stabilize mood enough for therapy to take hold. Waiting for therapy to work alone can be dangerous if symptoms are worsening. Don’t choose one over the other - think of them as partners.

What should I do if my teen says they feel worse after starting medication?

Call the prescribing doctor immediately. Don’t stop the medication on your own. Sometimes, symptoms get worse before they get better - especially in the first 1-2 weeks. The doctor may adjust the dose, switch medications, or add support. If your teen talks about suicide or has a plan, go to the emergency room or call 988. Never assume it’s just a phase.

Is the black box warning going to be changed?

Yes, a review is underway. As of late 2024, the FDA’s Psychopharmacologic Drugs Advisory Committee is evaluating new evidence. Many experts, including those from the American Psychiatric Association and AACAP, agree the warning should be revised to reflect that the benefits of antidepressants usually outweigh the risks for teens with moderate to severe depression. A more balanced warning - not a black box - is likely coming.

josue robert figueroa salazar

December 26, 2025 AT 13:34christian ebongue

December 27, 2025 AT 14:10jesse chen

December 28, 2025 AT 02:38Prasanthi Kontemukkala

December 28, 2025 AT 18:41Alex Ragen

December 30, 2025 AT 17:13Sarah Holmes

December 31, 2025 AT 10:34Michael Bond

December 31, 2025 AT 12:14carissa projo

January 2, 2026 AT 03:30Joanne Smith

January 3, 2026 AT 02:19Lori Anne Franklin

January 3, 2026 AT 06:34Bryan Woods

January 4, 2026 AT 02:02Ryan Cheng

January 5, 2026 AT 18:22wendy parrales fong

January 5, 2026 AT 21:51Matthew Ingersoll

January 7, 2026 AT 18:46Jody Kennedy

January 8, 2026 AT 19:43