When a patient switches from a brand-name drug to a generic, they often don’t just get a cheaper pill-they get a new belief. And that belief can change how their body responds, even when the chemistry is identical. This isn’t about bad science. It’s about the mind. The nocebo effect-the opposite of placebo-is real, powerful, and quietly undermining the benefits of generic drugs across the world.

What the Nocebo Effect Really Means

The nocebo effect happens when negative expectations cause real physical symptoms. It’s not imaginary. It’s biology. If a patient believes a pill will make them dizzy, nauseous, or tired, their brain can trigger those exact sensations-even if the pill contains zero active ingredients. In clinical trials, about 20% of people taking sugar pills report side effects. Nearly 10% quit the trial because of them. And when those sugar pills are labeled as "generic," the numbers jump even higher. A 2025 study tested this with sham oxytocin sprays. Healthy volunteers were told they were getting either a brand-name product (simple name, high price) or a generic (complex name, low price). Both sprays were identical-just saline. But those who thought they were using the generic reported more side effects. The difference wasn’t small. It was statistically significant. And it wasn’t because of the drug. It was because of the label. This isn’t just a lab trick. In the U.S., generics make up 90% of all prescriptions. Yet nearly 4 in 10 patients still worry they’re less effective. That fear isn’t irrational-it’s learned. From ads, from stories online, from doctors who say "I’d take the brand myself" without meaning to. And when patients feel unheard, their bodies pay the price.Why Packaging and Price Matter More Than You Think

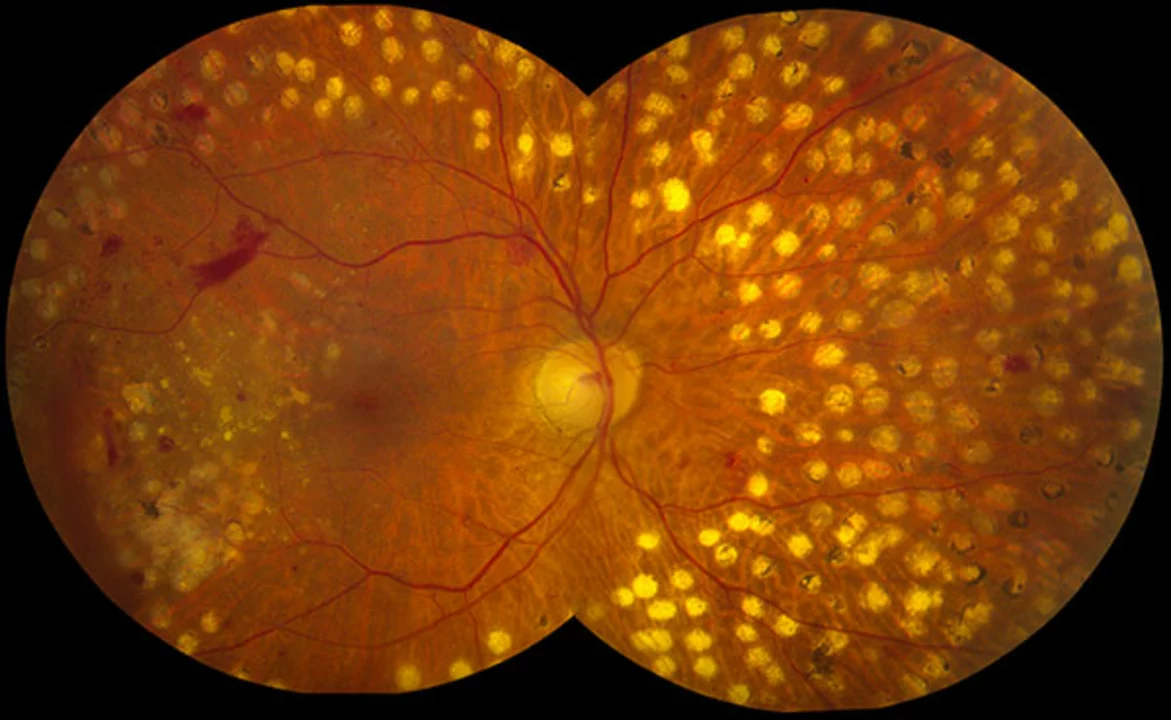

It’s not just the name. It’s the box. The color. The price tag. In one study, participants used a fake anti-itch cream. One group got it in a sleek blue box with a fancy name-"Solestan® Creme." The other got the same cream in a plain orange box labeled "Imotadil-LeniPharma Creme." Both had no active ingredient. But the group with the "expensive" cream reported more pain sensitivity. Why? Because they expected side effects from something cheap. Their brains interpreted normal sensations as harm. In New Zealand, when the brand venlafaxine switched to a generic version, reports of side effects didn’t spike at first. But after media outlets ran stories about "the generic that’s causing problems," calls to the national adverse reaction center surged. The drug hadn’t changed. The patients’ expectations had. Even the way a doctor says "I’m switching you to a generic" matters. If it’s said like an afterthought-"It’s cheaper, so we’ll try this"-patients hear: "This isn’t as good." But if it’s said like this-"This is the exact same medicine, just without the brand name. It’s been tested just as thoroughly"-the effect flips.How Bioequivalence Works (And Why It Doesn’t Fix Perception)

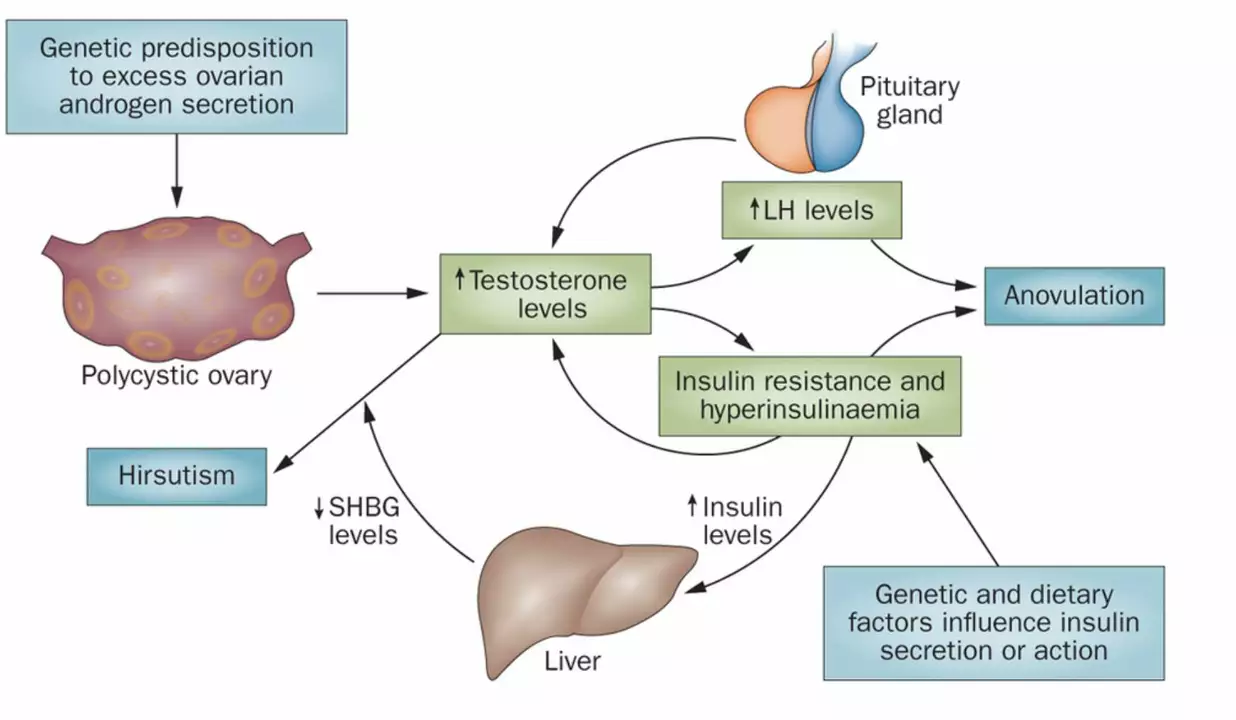

The FDA and other global regulators require generics to prove bioequivalence. That means the generic must deliver the same amount of active ingredient into the bloodstream as the brand, within a tight window-80% to 125% of the brand’s levels. In practical terms, it’s like two identical engines with different paint jobs. One runs on a $200 fuel filter. The other on a $5 one. Same performance. Same output. But patients don’t care about pharmacokinetic curves. They care about how they feel. If they’ve been on a brand for years and suddenly feel different after switching, they assume the generic is to blame-even when blood tests show identical drug levels. A 2023 study in PLOS Medicine found this clearly: patients reported more side effects on authorized generics-medications made by the same company, in the same factory, using the same formula as the brand-just sold under a different label. The only difference? The name on the bottle. That’s the nocebo effect in action. It’s not about quality. It’s about identity.

What Doctors and Pharmacists Can Do

The solution isn’t to stop prescribing generics. It’s to change how we talk about them. Here’s what works:- Use positive framing: Instead of saying, "This might cause nausea, dizziness, or headaches," say, "Most people tolerate this well. If you notice anything unusual, we’ll adjust it together."

- Explain bioequivalence simply: "This medicine has the same active ingredient, same strength, same way of working. The only difference is the cost. Studies show patients do just as well on it."

- Don’t hide the switch: If you’re changing the medication, tell them before it happens. Give them time to ask questions. Don’t surprise them at the pharmacy.

- Share the savings: A 2022 study found that telling patients they’d save over $3,000 a year-alongside reassurance about effectiveness-cut nocebo effects by 37%. Money matters, but so does trust.

- Use the right language: Say "generic medication" instead of "generic version." "Version" implies inferiority. "Medication" is neutral.

What Patients Should Know

If you’ve switched to a generic and started feeling worse, you’re not alone. But you’re not necessarily experiencing a new side effect. You might be experiencing a perceived one. Ask yourself:- Did anything else change around the same time? Stress? Sleep? Diet?

- Did I hear someone say the generic doesn’t work as well?

- Is the pill a different color or shape? (That’s normal-manufacturers can’t copy the brand’s appearance.)

Sarah Little

January 3, 2026 AT 23:52The nocebo effect in pharmacoeconomics is a fascinating epiphenomenon of cognitive dissonance mediated by pharmacokinetic expectancy schemas. When patients are primed with brand-associated heuristics, their limbic system amplifies somatic vigilance, resulting in psychosomatic symptom attribution despite bioequivalence. This isn't just perception-it's neurobiological conditioning reinforced by pharmaceutical marketing infrastructure.

JUNE OHM

January 4, 2026 AT 09:29THEY’RE LYING TO US. 😡 The brand-name companies own the generics now. Same factory. Same pills. But they slap a new label on it and make us think it’s trash. Then they laugh while we pay $500 for the ‘real’ one. The FDA? Controlled. The doctors? Paid off. I switched to generic and got migraines. Coincidence? Nah. 🤡💊 #BigPharmaLies

Philip Leth

January 5, 2026 AT 04:38Man, I used to think generics were just cheaper versions. Then my buddy switched from Lipitor to the generic and started feeling like a zombie. We both thought it was the meds. Turns out? He’d been watching YouTube videos about how generics are ‘cut-rate poison.’ He stopped taking it for a month, got his brand back, and felt fine. The pill didn’t change. His brain did. Wild, right?

Joy F

January 5, 2026 AT 09:10Let’s deconstruct this. The nocebo effect isn’t just psychological-it’s ontological. It reveals the collapse of the Cartesian divide between mind and body. When a pill’s identity is stripped of its symbolic capital (branding, color, price), the body rebels against the loss of narrative coherence. The generic isn’t inferior-it’s existential. It lacks the mythos that anchors our somatic trust. We don’t just take medicine-we consume meaning. And when that meaning is erased, the body screams into the void. 🌀

And let’s not pretend doctors are innocent here. When they say, ‘It’s just cheaper,’ they’re not just informing-they’re devaluing. The language itself is a microaggression against biological agency. The real scandal isn’t the pill. It’s the epistemic violence of clinical discourse.

Meanwhile, Big Pharma quietly rebrands generics as ‘authorized equivalents’ with premium packaging. The solution isn’t education-it’s semiotic reclamation. We need to restore the sacred aura of the pill. Or else, we’re just pharmacological nihilists.

Ian Detrick

January 5, 2026 AT 21:24This is the most important thing I’ve read all year. We’re so focused on the science of meds that we forget the human part-the fear, the stories, the shame of taking something ‘cheap.’ I’m a nurse, and I’ve seen patients cry because they think they’re ‘settling’ for a worse drug. We need to change how we talk about this. Not with jargon. Not with stats. With dignity. Every patient deserves to feel like they’re getting the best, no matter the price tag.

Brittany Wallace

January 6, 2026 AT 13:02My mom switched to generic metformin last year and started blaming it for her joint pain. She was convinced it was ‘weaker.’ I showed her the FDA page, the bioequivalence charts, even the manufacturer info-it’s the same factory as the brand. She still didn’t believe it. Then I told her she saved $800 this year. She paused. Said, ‘Huh. Maybe I’m just mad I didn’t know I could’ve been doing this for years.’ Sometimes it’s not about facts. It’s about feeling like you got a good deal. 💙

Michael Burgess

January 8, 2026 AT 12:15Bro, I work in a pharmacy. Every day someone comes in mad because their ‘new’ pill is a different color. They’re convinced it’s fake. I hand them the bottle, point to the active ingredient, and say, ‘This is the same thing your doc prescribed-just cheaper.’ Half the time, they just nod and leave. But the ones who stick around? They’re usually scared. Not stupid. Just scared. We need to stop treating them like they’re dumb and start treating them like humans who’ve been sold a lie for 20 years. 🙏

Lori Jackson

January 9, 2026 AT 15:56Of course the nocebo effect exists. But let’s be real-most people aren’t ‘misinformed.’ They’re just smarter than the system gives them credit for. Generics are often made in overseas factories with sketchy oversight. The FDA’s 80-125% bioequivalence window? That’s a legal loophole, not a guarantee of safety. People sense this. Their bodies react because they’ve seen the headlines. This isn’t ‘perception.’ It’s intuition. And you can’t cure intuition with a script.

innocent massawe

January 10, 2026 AT 16:07In Nigeria, we don’t have brand-name drugs most of the time. We just take what’s available. No one cares about the label. If it works, it works. Maybe the problem isn’t the patient. Maybe it’s the culture that says ‘expensive = better.’ Here, we don’t have that luxury. We have trust in the medicine, not the box.

veronica guillen giles

January 12, 2026 AT 02:54Oh sweet mercy, here we go again with the ‘just talk to them better’ solution. 🙄 So let me get this straight-we’re going to fix systemic healthcare inequality by teaching doctors to say ‘generic medication’ instead of ‘generic version’? Brilliant. Meanwhile, people are choosing between insulin and rent. Maybe if we stopped making meds unaffordable in the first place, people wouldn’t need a therapist to tell them their pill isn’t evil.