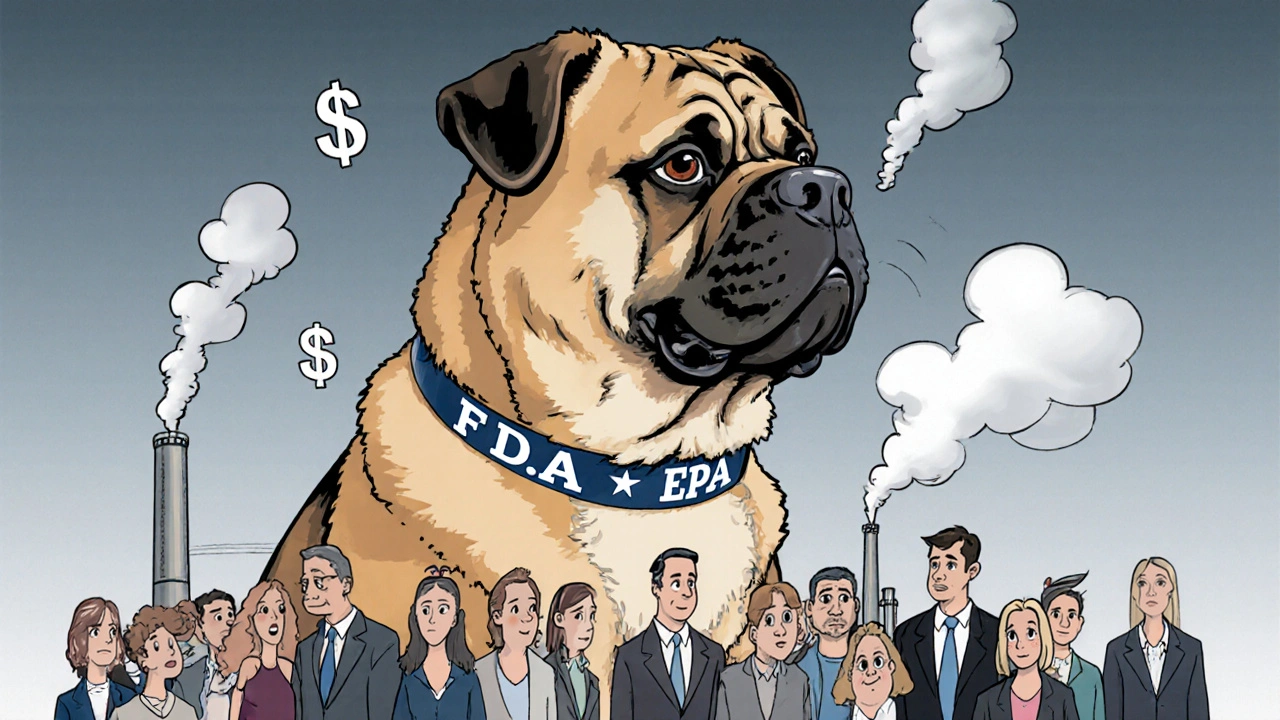

When you think of government regulators, you probably imagine watchdogs protecting you - from unsafe drugs, dirty air, rigged financial markets, or power companies overcharging your bill. But what if those watchdogs have become part of the pack? That’s the quiet, dangerous reality of regulatory capture.

Regulatory capture isn’t corruption in the classic sense. You won’t always see cash changing hands in a back room. Instead, it’s a slow, systemic shift where the agencies meant to serve the public start acting like they work for the industries they’re supposed to control. It happens when the line between regulator and regulated blurs - not because of evil intent, but because of familiarity, dependency, and power imbalances that favor the few over the many.

How Regulatory Capture Works: The Three Main Ways

There are three main paths to capture, and they often overlap.

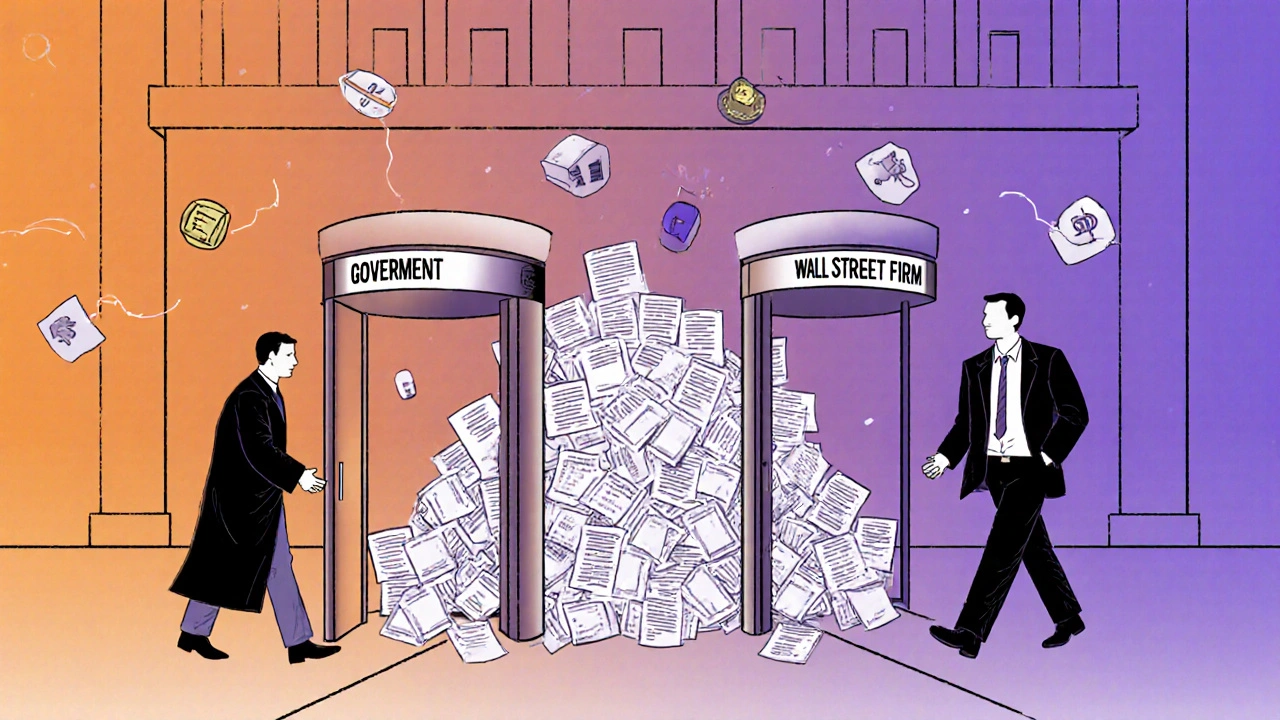

The first is materialist capture. This is when regulators get tempted - or pressured - by money, jobs, or favors. The most visible version is the revolving door: a senior official leaves the FDA to become a lobbyist for a drug company, or an EPA engineer joins a coal firm. A 2022 study found that 92% of former SEC commissioners took jobs with Wall Street firms within 18 months of leaving office. Between 2008 and 2018, 53% of top officials at the U.S. Department of Defense went straight into defense contracting. These aren’t coincidences - they’re incentives. Regulators know their next job depends on playing nice.

The second is cultural capture. This is quieter but just as damaging. Over time, regulators start thinking like the people they regulate. They attend the same conferences, drink the same coffee, share the same technical jargon. They begin to believe that what’s good for the industry is good for the public. A 2021 study found agencies with formal industry advisory panels were 3.7 times more likely to adopt rules that favored those industries. Why? Because the industry’s perspective becomes the default. The regulator no longer asks, “What protects the public?” - they ask, “What’s feasible for the company?”

The third is information asymmetry. Modern industries - think pharmaceuticals, fintech, or energy - are incredibly complex. Regulators don’t have the staff or expertise to understand every technical detail. So they rely on the industry to provide the data, the models, the safety reports. And guess who writes those reports? The companies themselves. When the regulator depends on the regulated for basic facts, it’s not oversight - it’s delegation. The FAA, for example, delegated 96% of safety reviews for the Boeing 737 MAX to Boeing employees. That’s not a flaw in the system. That’s how the system was designed.

Real Cases: When Regulation Fails the Public

History is full of examples where capture led to real harm.

The Interstate Commerce Commission was created in 1887 to protect farmers from railroad monopolies. By 1900, it was raising shipping rates at the railroads’ request. The regulators didn’t become corrupt - they became comfortable. The railroads were the only ones who showed up to hearings. The farmers didn’t. So the rules changed.

In 2008, the Securities and Exchange Commission failed to stop the financial collapse. Why? Because staff had personal ties to 87% of the biggest Wall Street firms. They didn’t investigate aggressively. They didn’t question risky derivatives. They trusted the people they’d worked with - or hoped to work for.

The U.S. sugar industry is a textbook case of how capture benefits a few at the expense of millions. Thanks to tariffs and quotas, American consumers pay about three times the global price for sugar. That’s $3.9 billion a year taken out of household budgets. Who wins? Just 4,318 sugar producers. They make $1.2 billion extra annually. The cost is spread so thin - $33 per household - that no one feels it enough to fight back. Meanwhile, the sugar lobby spends 22 times more on political contributions than consumer groups. The math is clear: concentrated profits, dispersed pain = easy capture.

Even in healthcare, the pattern repeats. The FDA has been accused of approving drugs with weaker evidence than the EU. One former employee, posting anonymously on Reddit, claimed his company routinely got approvals with 60% less clinical data than required overseas. Public Citizen found that 73% of former EPA officials who left between 2010 and 2020 joined fossil fuel companies. The agency’s enforcement actions slowed by 28 days during those transitions.

Why It’s So Hard to Fix

Why don’t we just fix this?

Because the system is designed to resist change.

First, industry has more money, more time, and more motivation. In OECD countries, industry groups spend 17.3 times more per person on lobbying than consumer advocates. They hire former regulators. They fund think tanks. They show up at every hearing. The public? Most people don’t even know a rule change is happening until their electric bill goes up.

Second, the rules meant to prevent capture are weak. The U.S. Ethics in Government Act requires a “cooling-off period” before former officials can lobby their old agency. But 41% of violations go unpunished. The EU’s Transparency Register? Only 32% of big corporations even bother to comply.

Third, the complexity of modern industries makes oversight nearly impossible. Regulating cryptocurrency means understanding 1,842 technical protocols. Regulating AI-driven financial tools requires knowing how algorithms make decisions - and who programmed them. Regulators are outnumbered and outgunned.

Even well-intentioned reforms often fail. Between 2015 and 2022, 78% of proposed anti-capture laws in the U.S. died in committee. Why? Because the people who benefit from the status quo - the industry insiders - are the ones writing the bills.

What’s Being Done - and What Actually Works

Some places are fighting back.

New Zealand introduced an independent process for reviewing regulations in 2016. Before, 68% of new rules favored industry. Now, that number is down to 31%. How? By requiring public input, forcing agencies to justify every rule, and banning industry-only advisory panels.

Canada’s “Regulatory Integrity Training” program taught regulators to limit private meetings, document all contacts, and actively seek out consumer voices. Result? Industry meetings dropped by 27%. Public consultations went up by 43%.

France’s “Convention Citoyenne pour le Climat” brought together 150 randomly selected citizens to draft climate policy. Their recommendations cut energy industry influence on the final plan by 52%. Why? Because the public, not the lobbyists, got to write the rules.

The U.S. Federal Trade Commission launched its own “Regulatory Capture Initiative” in March 2023. It now requires 100% disclosure of all industry contacts and created a new Office of Regulatory Integrity with a $23 million budget. Early signs are promising - but it’s too soon to say if this will stick.

What You Can Do

You might feel powerless. But you’re not.

When a new rule is proposed - say, for drug pricing, air quality, or bank fees - public comment periods are open. Most people ignore them. You don’t have to. A single comment from a real person, citing personal impact, carries more weight than 10,000 automated industry letters.

Support watchdog groups like Public Citizen, Consumer Reports, or the Center for Responsive Politics. They track the revolving door. They expose conflicts. They push for transparency.

Vote for candidates who don’t take industry money. Ask them: “Will you ban former regulators from joining the industries they once oversaw?” If they hesitate, they’re already part of the system.

Regulatory capture isn’t inevitable. It’s a choice. And choices can be reversed - if enough people care enough to act.

What is regulatory capture?

Regulatory capture occurs when government agencies created to protect the public end up serving the interests of the industries they regulate. This happens not through obvious corruption, but through subtle influences like revolving doors, industry-funded data, prolonged relationships, and unequal access to political power.

Is regulatory capture the same as bribery?

No. While bribery involves direct illegal payments, regulatory capture is often legal and systemic. It’s about influence - through job offers, shared perspectives, information control, and lobbying - rather than cash in envelopes. A regulator might never take a bribe, but still push rules that help their future employer.

Which industries are most prone to regulatory capture?

According to the World Bank’s 2022 report, the financial sector has the highest capture rate at 67%, followed by energy (58%) and pharmaceuticals (52%). These industries have high profits, complex regulations, and strong lobbying power. They also benefit from dispersed costs - millions pay a little extra, while a few companies gain billions.

How does the revolving door contribute to capture?

The revolving door creates a powerful incentive. Regulators know that if they’re too strict, they won’t get a high-paying job in the industry after leaving government. This leads to softer rules, delayed enforcement, and less scrutiny. Studies show that 92% of former SEC commissioners joined regulated firms within 18 months of leaving office.

Can regulatory capture be stopped?

Yes - but it requires structural changes. Successful efforts include banning industry-only advisory panels, requiring full public disclosure of all regulator-industry contacts, enforcing cooling-off periods, and empowering independent oversight bodies. Citizen-led processes, like France’s climate convention, have also proven effective by replacing industry voices with ordinary people.

Why don’t more people know about regulatory capture?

Because its effects are hidden. You don’t see a scandal - you just pay more for sugar, drugs, or electricity. The cost is spread across millions, so no one feels it strongly enough to protest. Meanwhile, the winners - the corporations - spend millions to keep the system quiet. The lack of media attention isn’t an accident. It’s by design.

Eric Healy

November 16, 2025 AT 23:02Regulatory capture isn't some conspiracy theory - it's the fucking operating system. They don't need bribes when the whole damn revolving door is greased with promises of six-figure lobbyist gigs. You think the FDA's slow on drug approvals? Nah, they're just waiting for their next job at Pfizer. It's not corruption, it's capitalism with a side of institutional cowardice.

Shannon Hale

November 17, 2025 AT 10:26OH MY GOD. THIS IS EXACTLY WHY I CAN'T TRUST ANYTHING ANYMORE. I PAY $18 FOR A BOTTLE OF IBUPROFEN THAT COSTS 75 CENTS TO MAKE AND THE FDA LETS IT HAPPEN BECAUSE SOME FORMER REGULATOR IS NOW A VP AT PFIZER?!?!?! THIS ISN'T JUST BROKEN, IT'S A CRIMINAL SYNDICATE WITH A FEDERAL SEAL ON IT. WE NEED TO BURN THE WHOLE SYSTEM DOWN AND START OVER WITH A CROWDSOURCED REGULATORY BOARD OF RANDOM CITIZENS WHO CAN'T EVEN SPELL 'PHARMACEUTICAL'.

Holli Yancey

November 17, 2025 AT 10:40I get why this feels overwhelming. I used to work in public health policy, and the pressure to 'be reasonable' with industry reps was constant. It's not that people are evil - it's that the system rewards conformity. But I've seen small wins: a local health department that started requiring all industry meetings to be live-streamed. It didn't fix everything, but it made people think twice. Change doesn't have to be massive to matter.

Gordon Mcdonough

November 18, 2025 AT 08:57Jessica Healey

November 18, 2025 AT 11:34Remember when they let those toxic baby formula companies get away with it? Same damn thing. They give you a study that says it’s 'safe' but it’s written by their in-house team who got paid by the same company that made the product. And then you get mad when your kid ends up in the hospital. It’s not a glitch. It’s the design.

Levi Hobbs

November 19, 2025 AT 07:12I really appreciate how you laid out the three types of capture - materialist, cultural, and information asymmetry. It’s so easy to think of corruption as just bribery, but this is way more insidious. I’ve seen cultural capture firsthand in my agency - people start quoting industry talking points like they’re gospel. Maybe the solution isn’t just more rules, but mandatory rotation between public and private sectors so no one gets too cozy. And maybe public comment periods should be weighted - real personal stories get priority over corporate boilerplate.

henry mariono

November 19, 2025 AT 07:23It’s a quiet tragedy. The people who care enough to show up at hearings are almost always the ones with something to gain. The rest of us are just trying to pay bills and get through the day. I don’t have the energy to fight it. But I do hope someone does.

Sridhar Suvarna

November 20, 2025 AT 17:50In India, we face similar challenges with pharmaceutical regulation. But we have a unique advantage: millions of citizens who are deeply affected by drug prices. When public outrage becomes visible - through protests, social media, or even court petitions - even captured agencies blink. The key is not to wait for perfect systems. Start with local transparency. Share the data. Name the names. Make it impossible to ignore.

Joseph Peel

November 20, 2025 AT 22:19France’s Citizen Convention for the Climate is the most promising model I’ve seen. Not because it’s perfect, but because it breaks the monopoly of expertise. When 150 randomly selected people - no lobbyists, no PhDs, no corporate ties - draft policy, the outcome is fundamentally different. The industry didn’t get to write the script. The public did. That’s not just reform. That’s a revolution in governance.

Kelsey Robertson

November 21, 2025 AT 02:45Wait - so you’re telling me the system isn’t broken? It’s working exactly as designed? Then why are we pretending this is a problem that needs fixing? Maybe the real issue is that we’re still operating under the delusion that government exists to serve the people. Newsflash: it doesn’t. It exists to serve the people who show up with the most money, the most lawyers, and the most connections. The rest of us are just background noise. And honestly? That’s the only honest truth here.